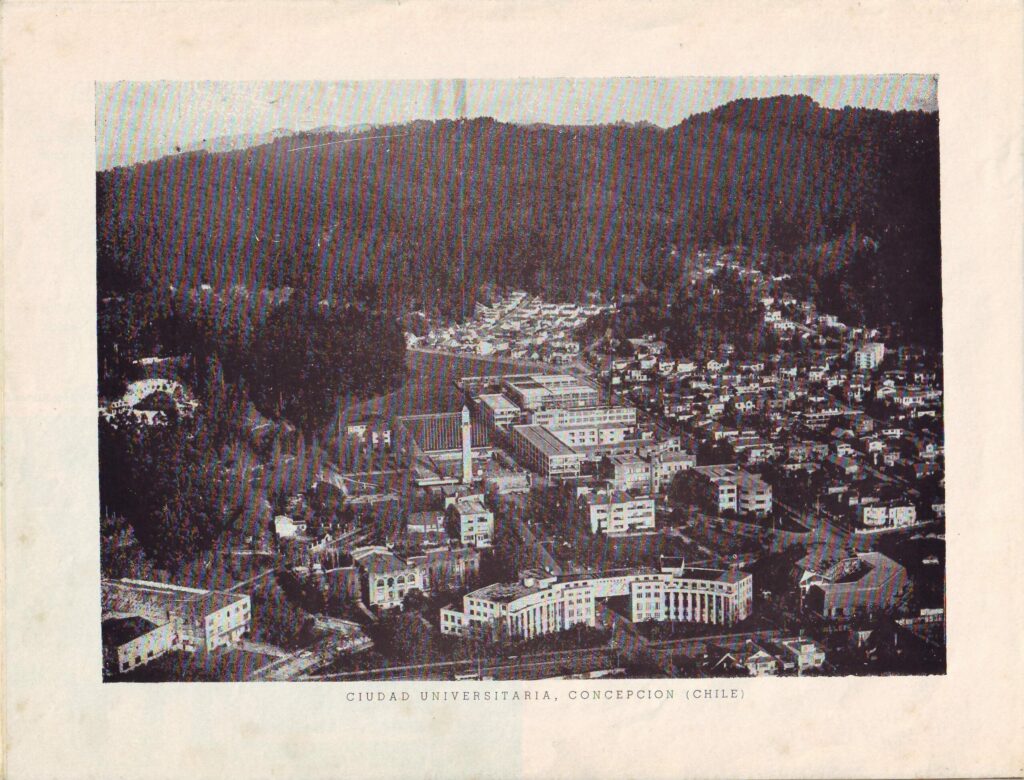

The Chilean-Mexican Plan for Fraternal Cooperation, 1960–1964, was created due to the great catastrophe caused by the earthquake that struck in May 1960. Mexico, like other nations, came to Chile’s assistance after the region was devastated by the most catastrophic earthquake in recorded history.

As soon as time-sensitive matters were resolved, the Chilean Mexican Plan was seen as an example of enduring and fruitful cooperation between two neighboring nations. This plan was created primarily in the eight provinces and sixteen cities impacted from Puerto Montt to Valparaiso. Mexico conveyed its aid by plane and, primarily, on the ship ‘Tabasco’, which divided the assistance into two sections: the first part was immediate aid provided to southern Chile between August and December 1960. The second type of assistance consisted of essential consumer goods and building materials.

The plan intended an end date of November 2, 1964, which corresponded to the conclusion of H.E. Jorge Alessandri Rodriguez’s constitutional term as president of Chile. It was also coincident with the expiration of Mr. Adolfo López Mateos’s term as president of Mexico, which occurred on December 1 of the same year.

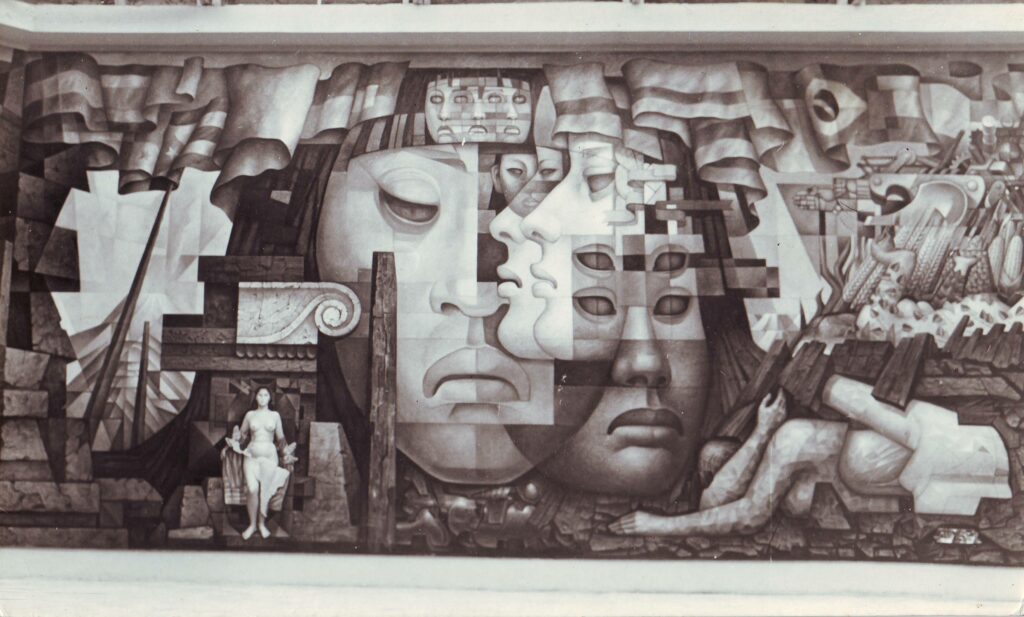

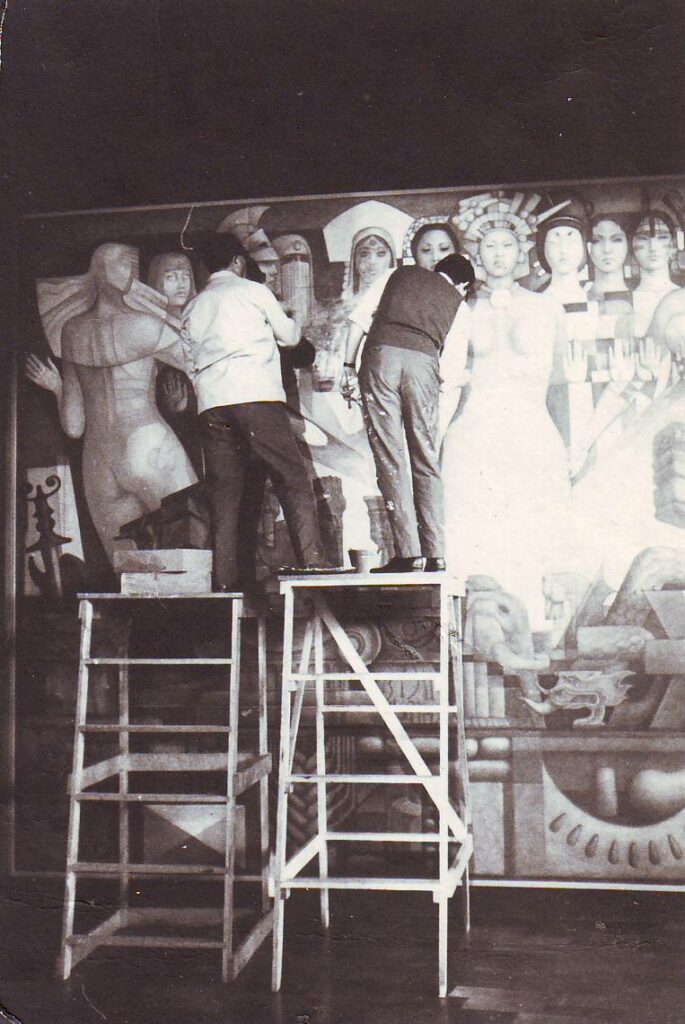

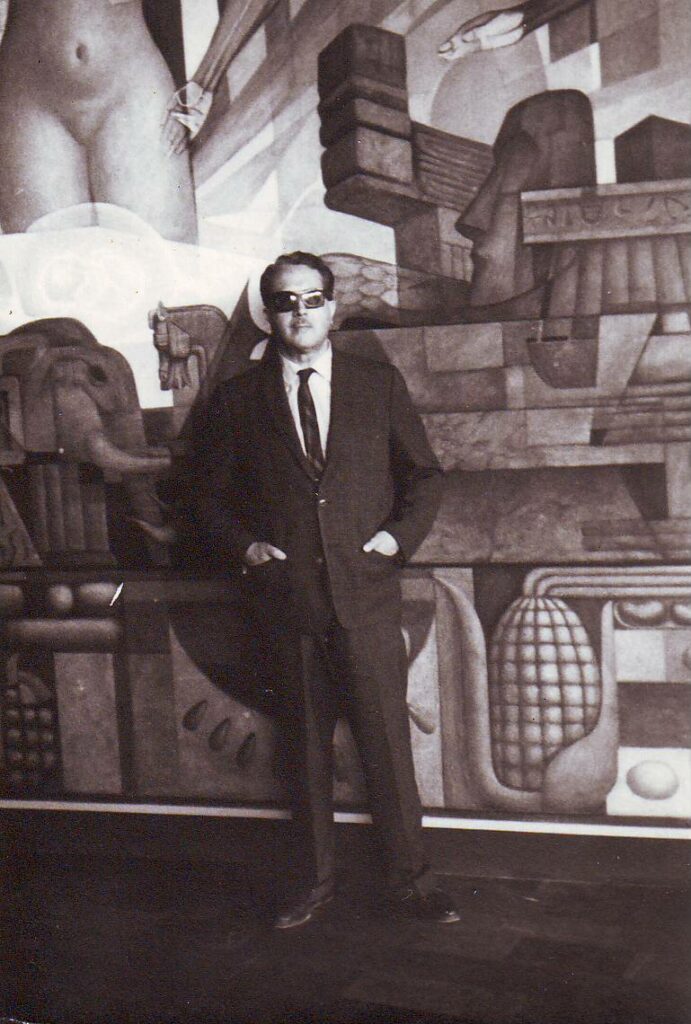

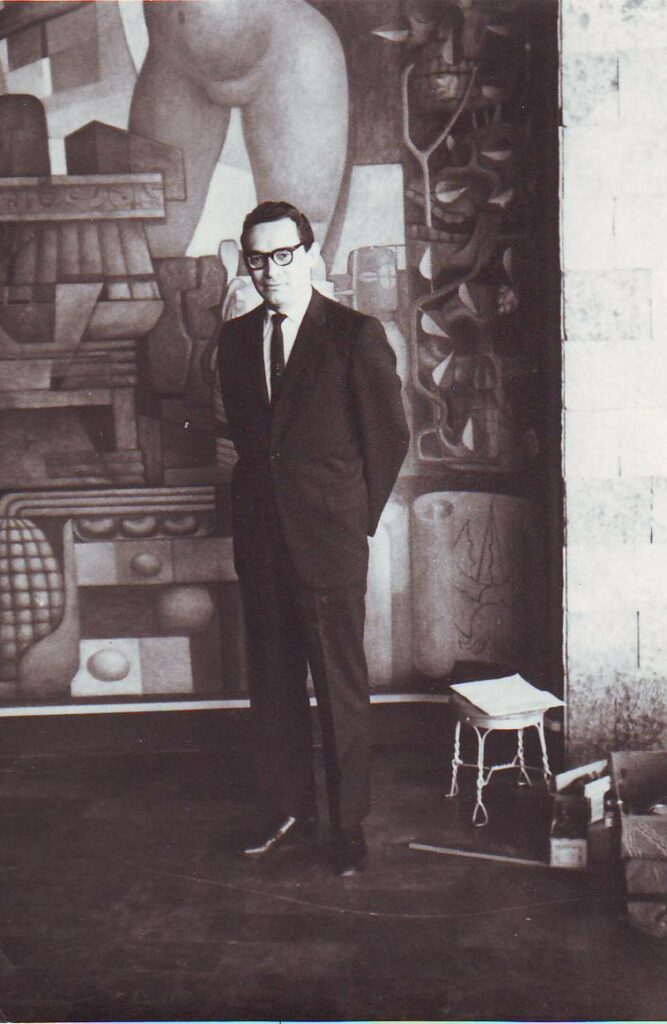

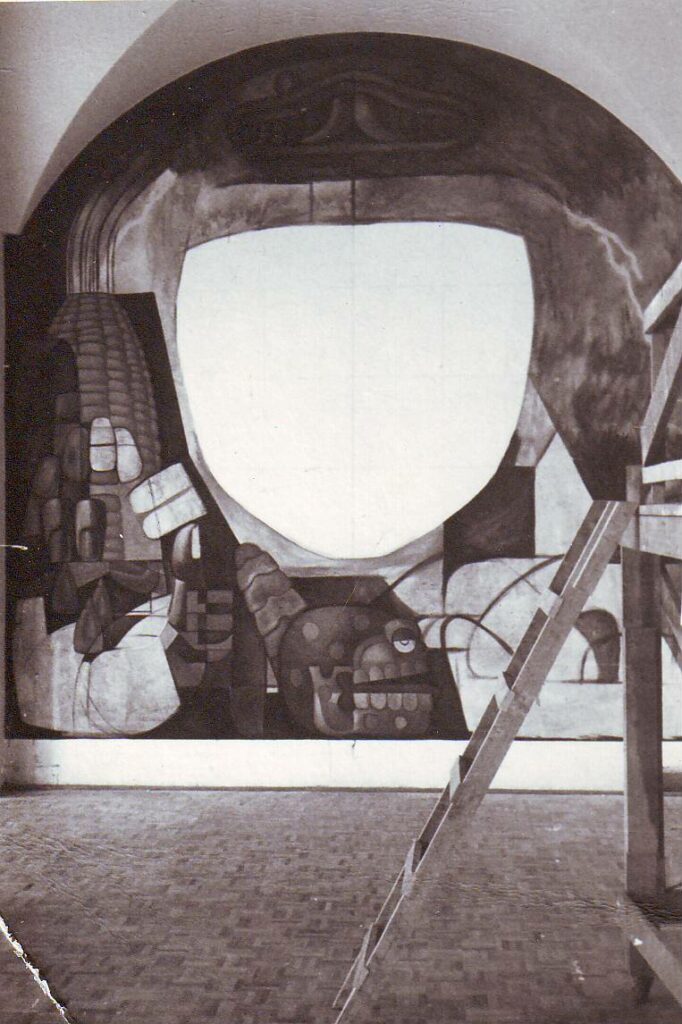

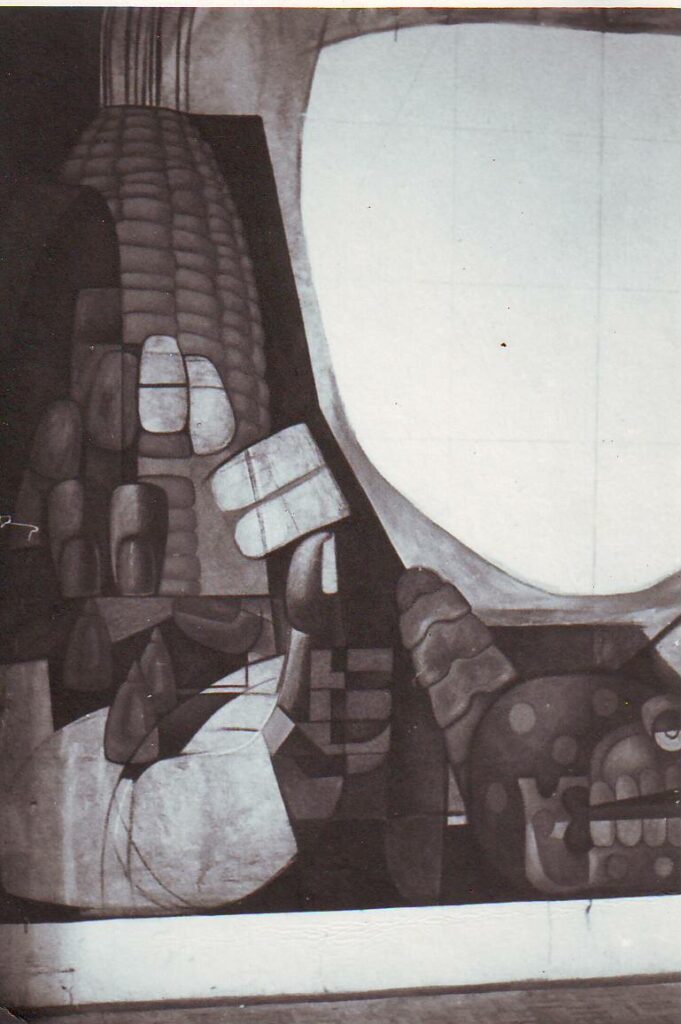

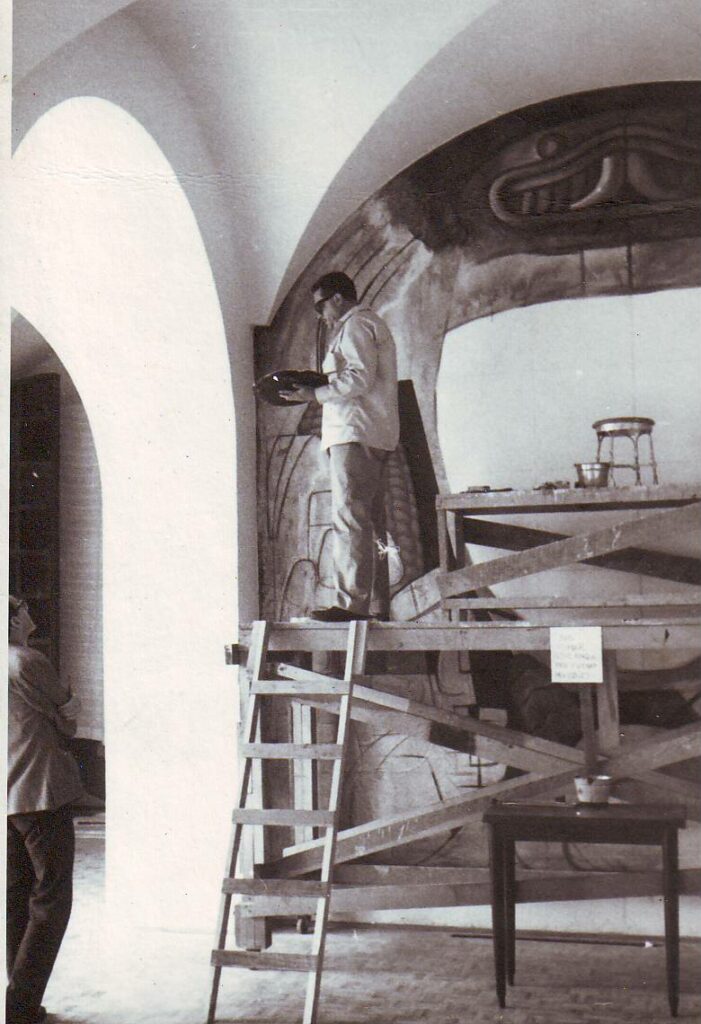

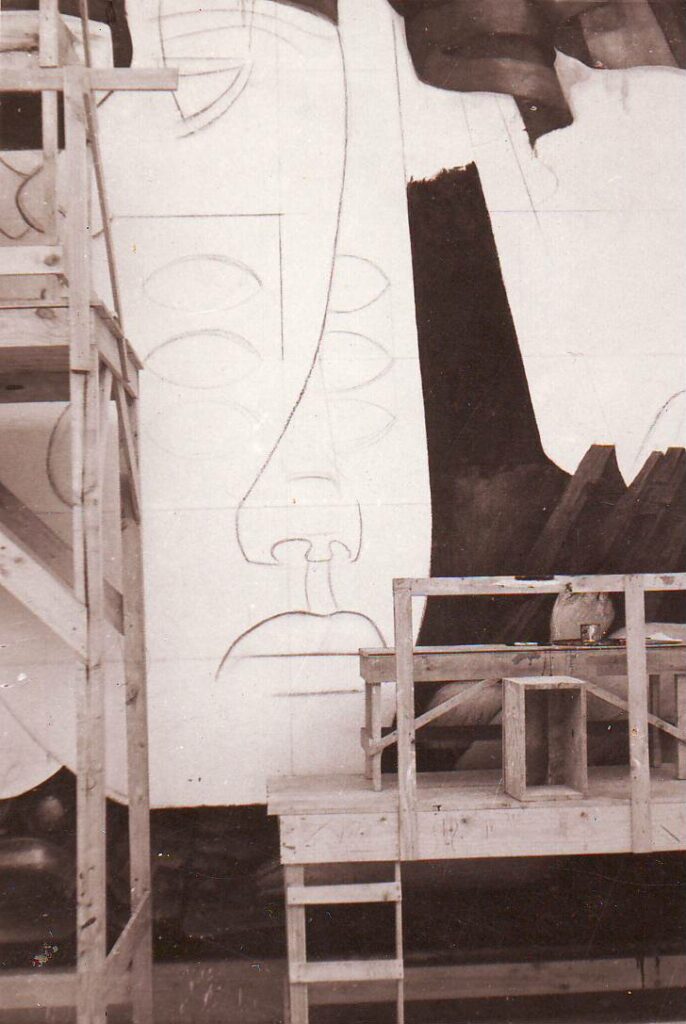

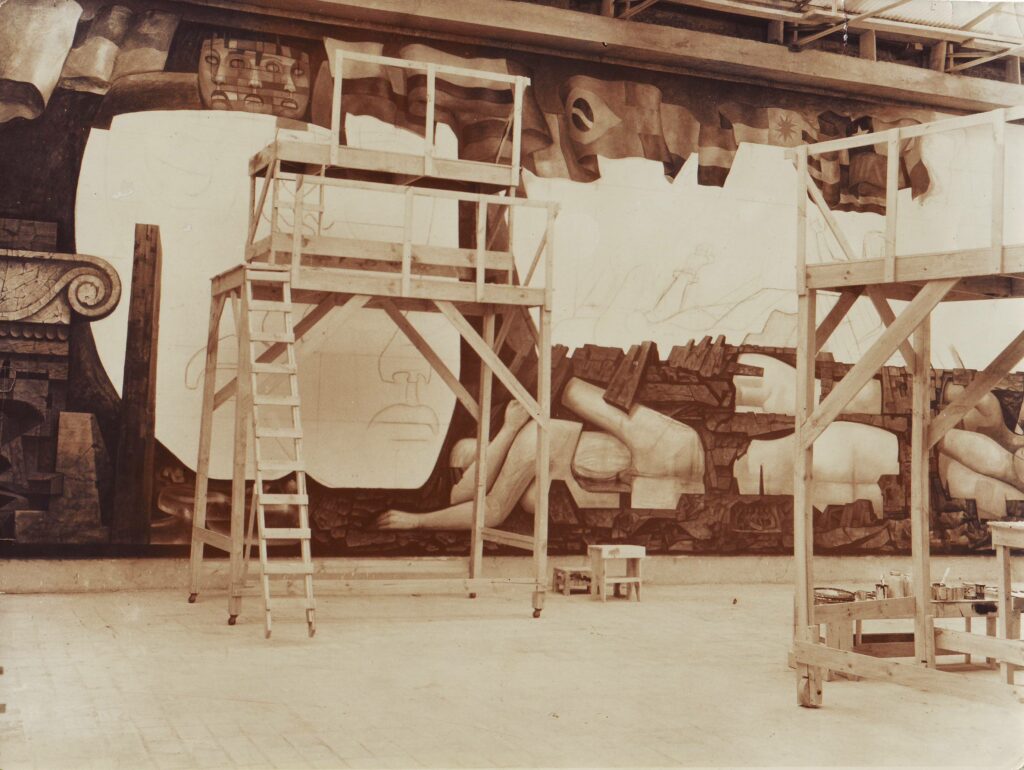

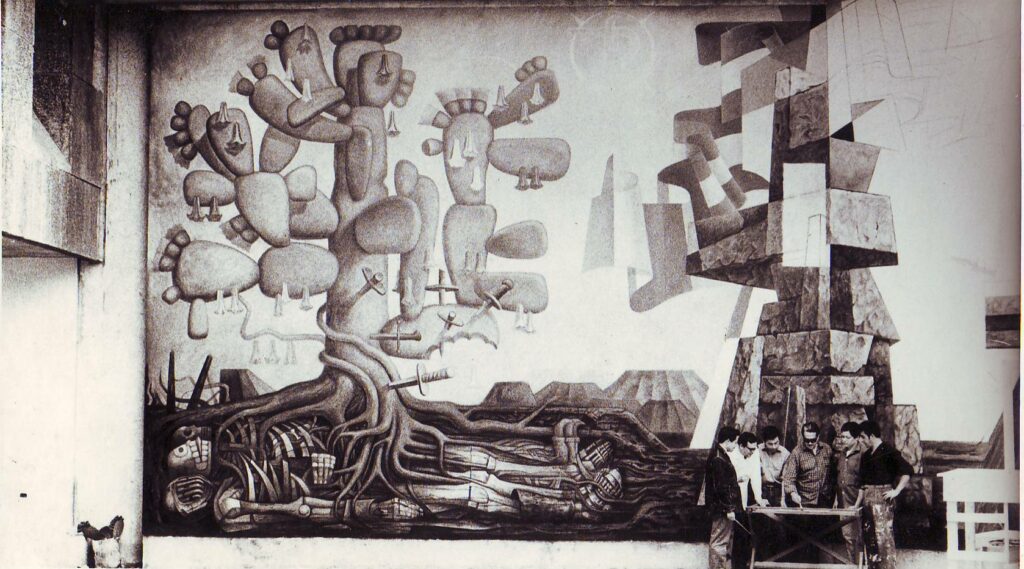

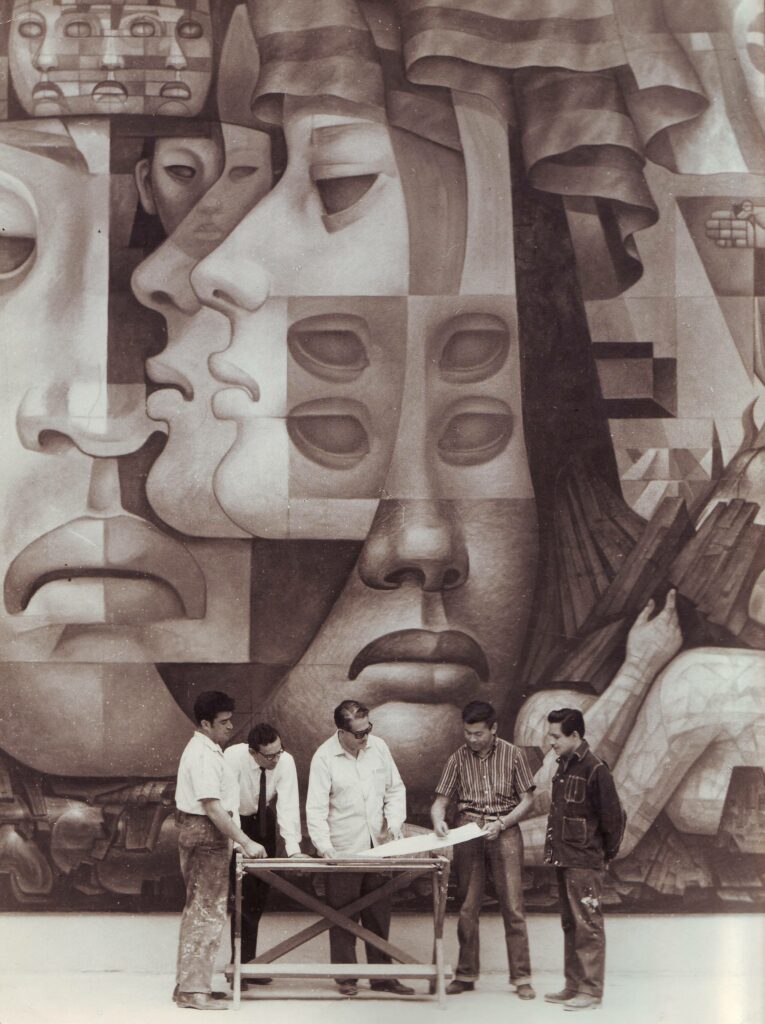

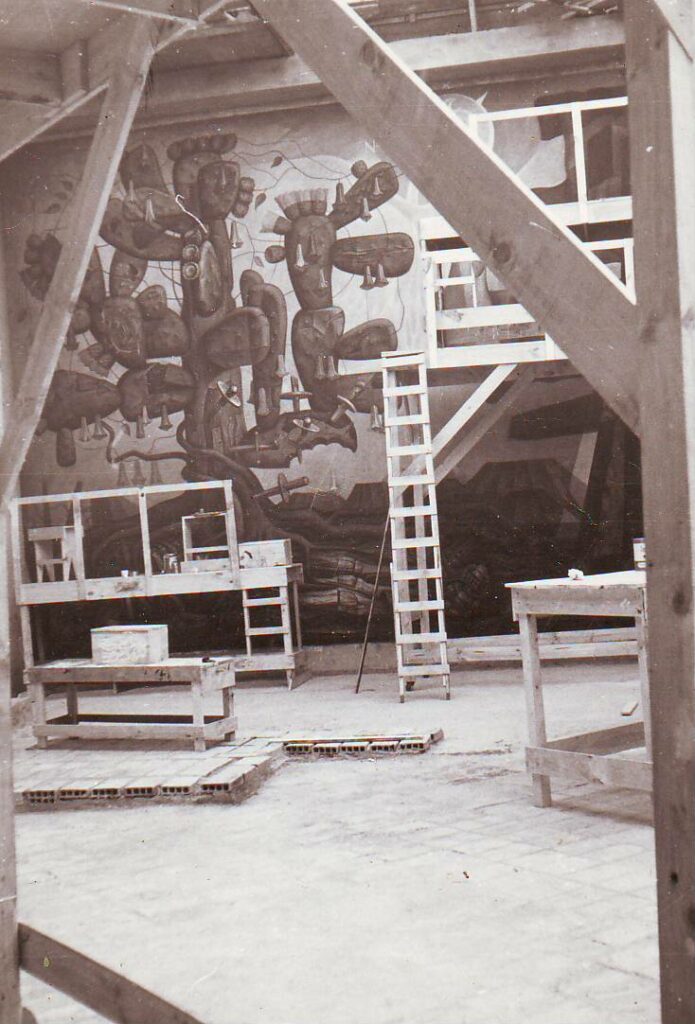

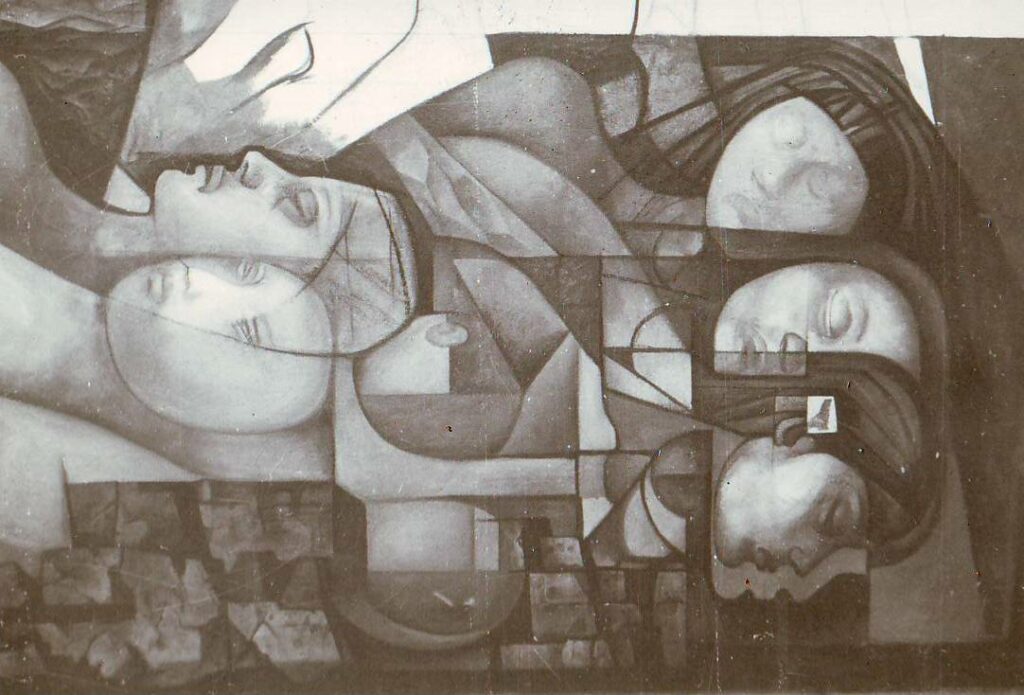

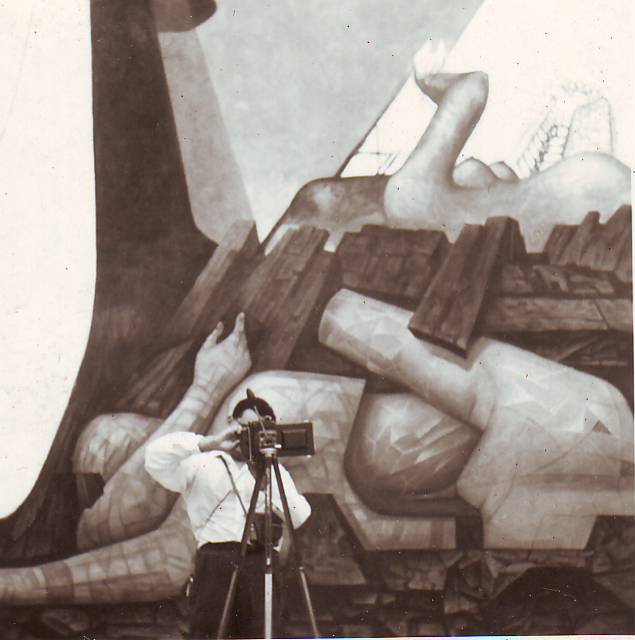

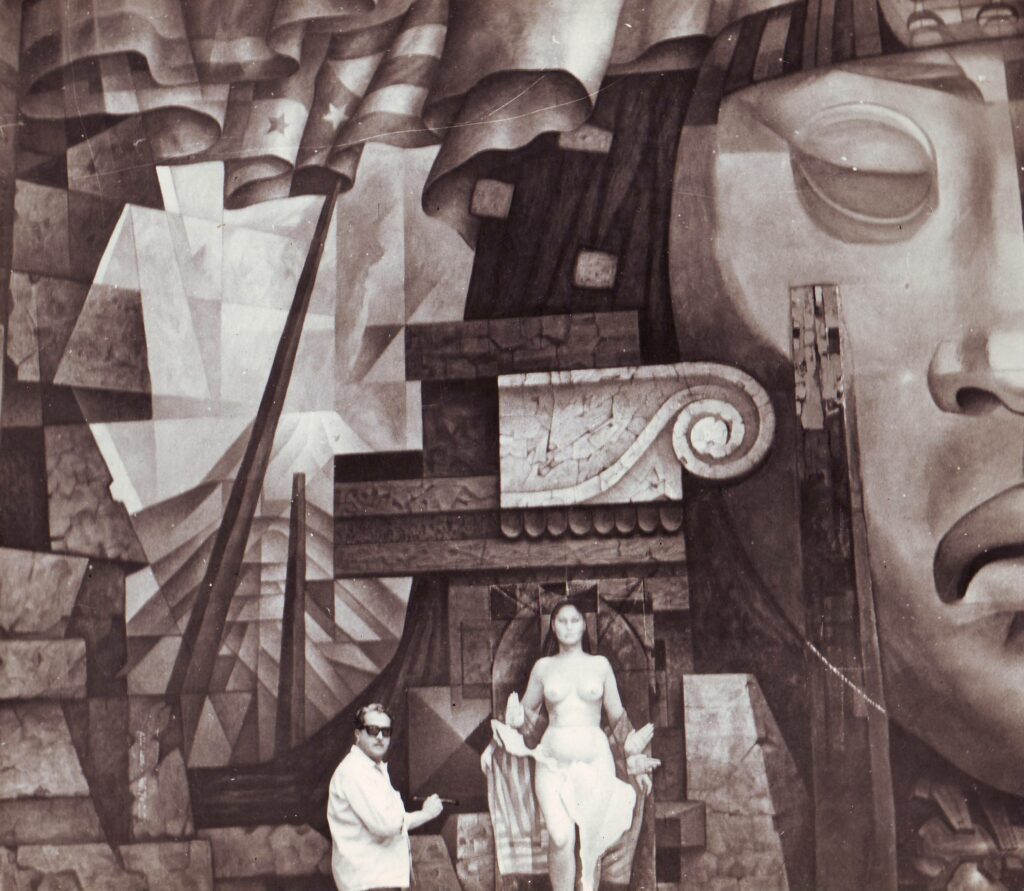

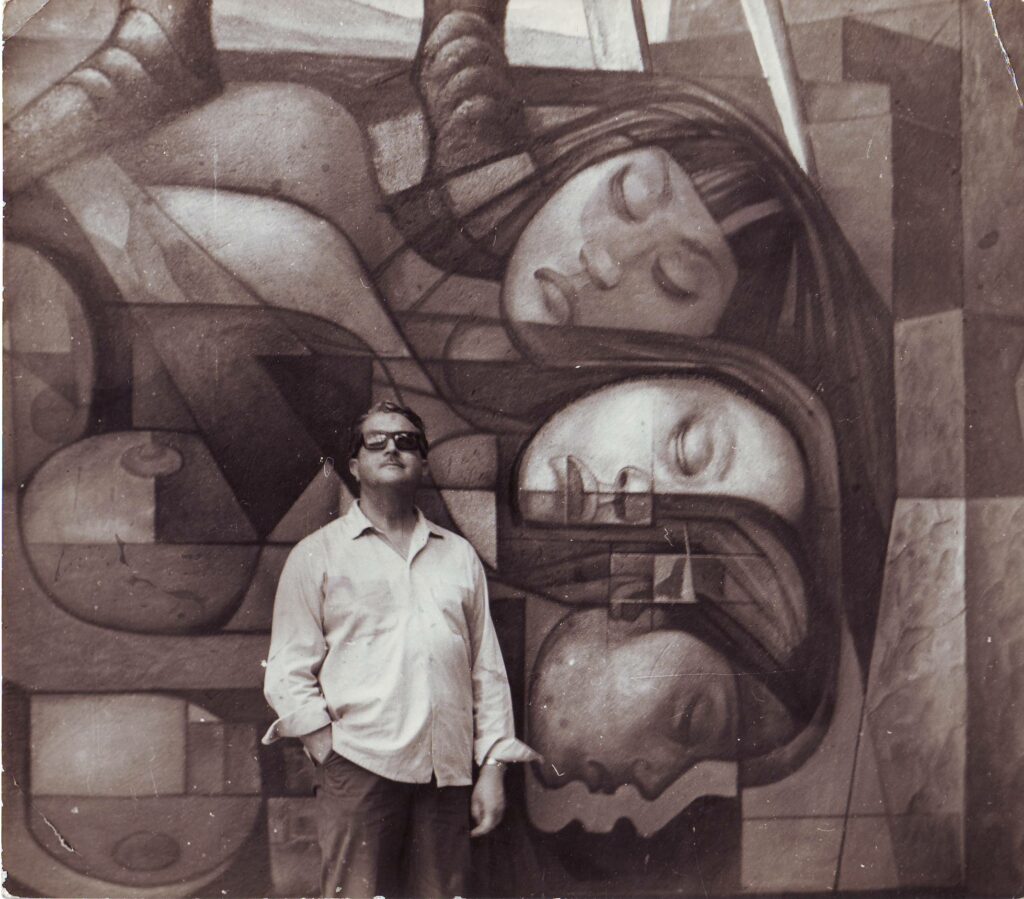

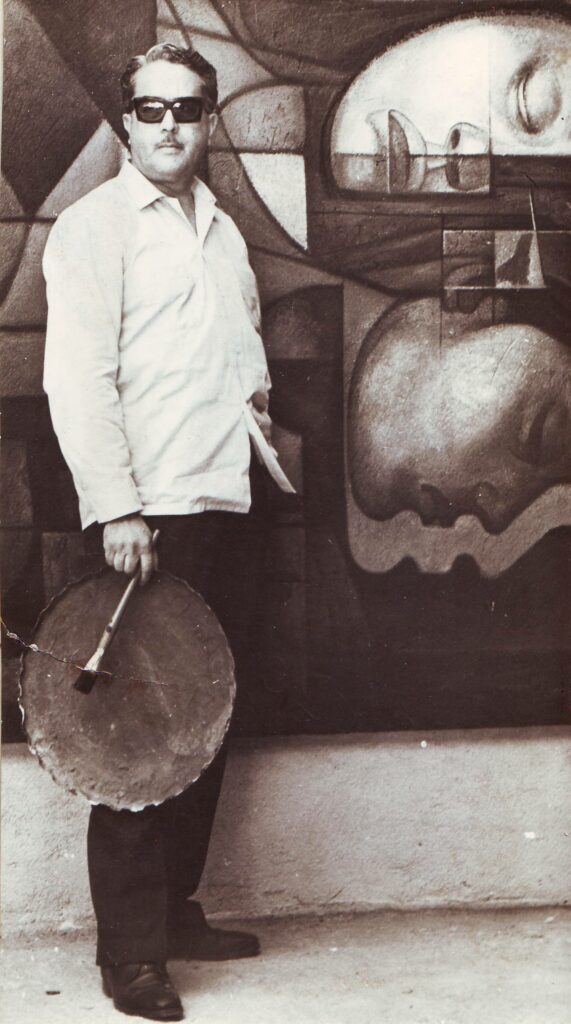

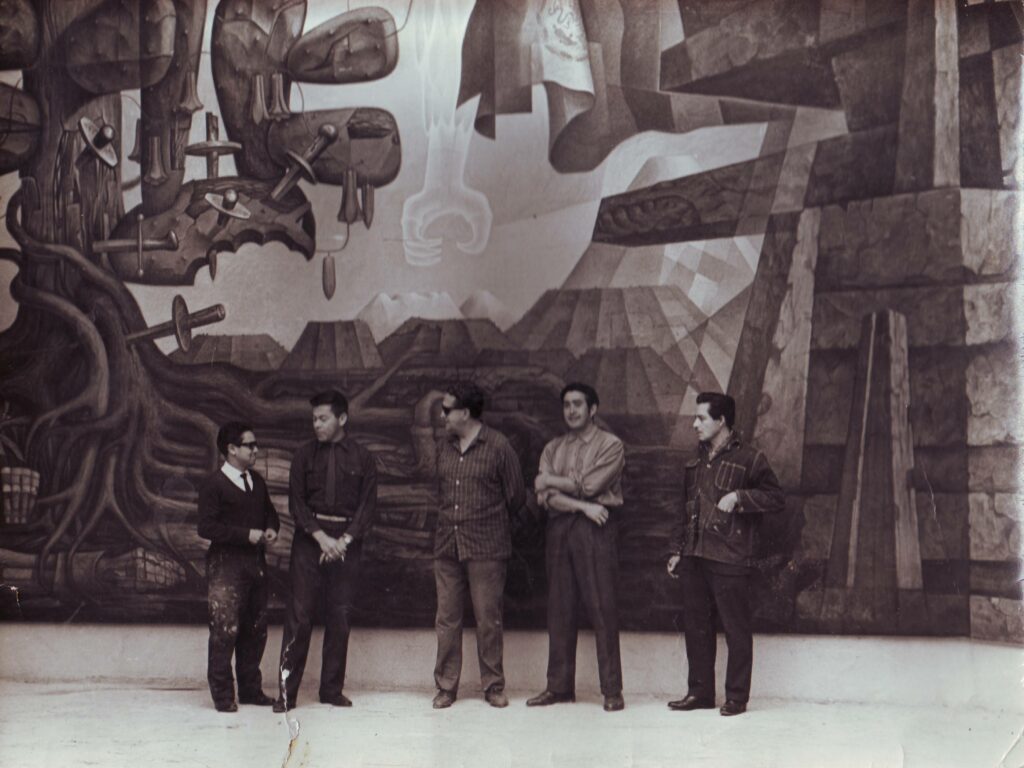

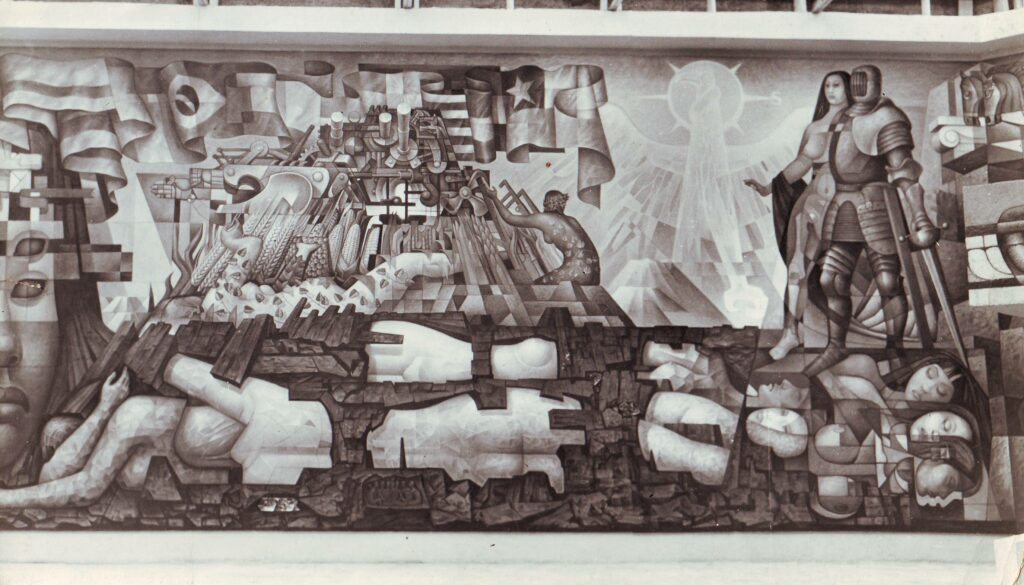

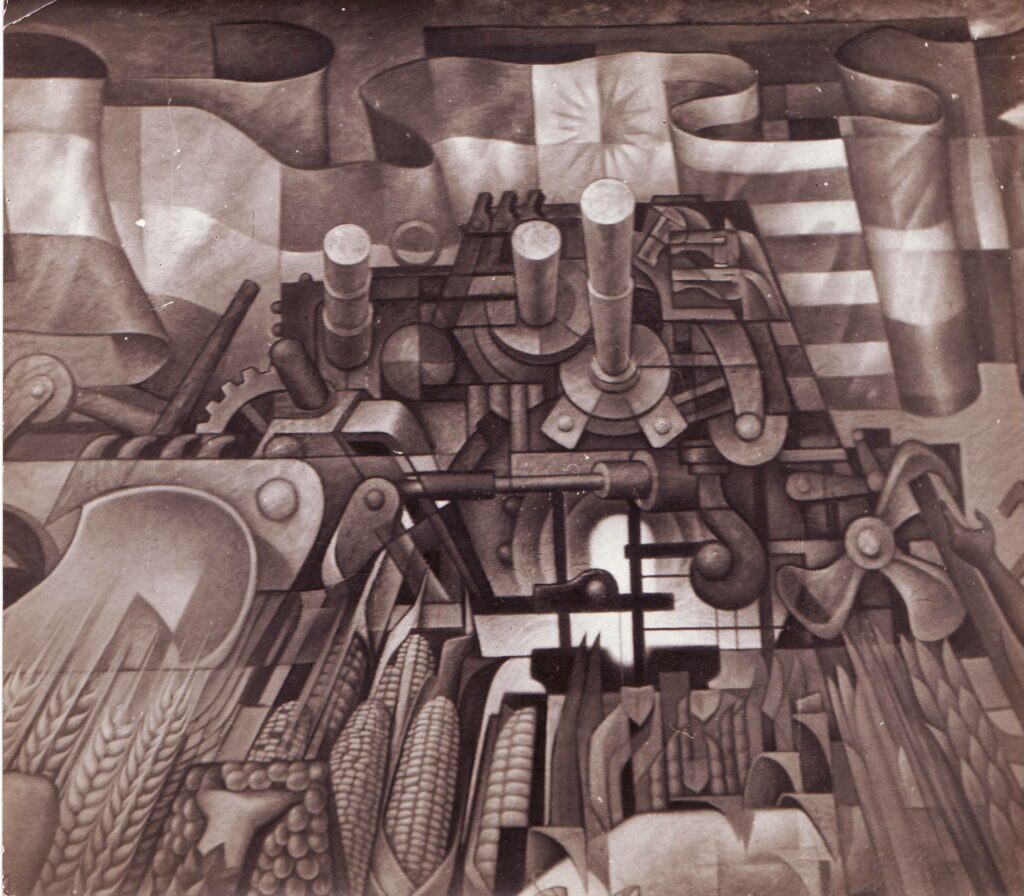

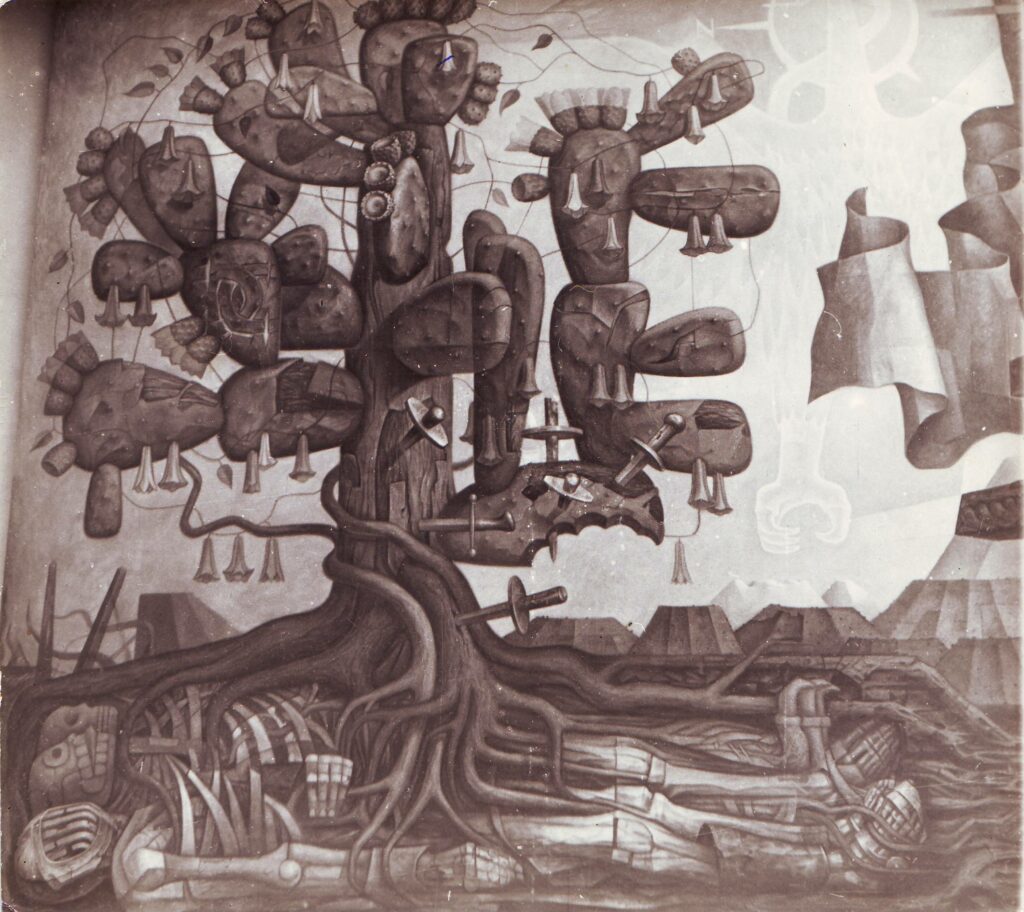

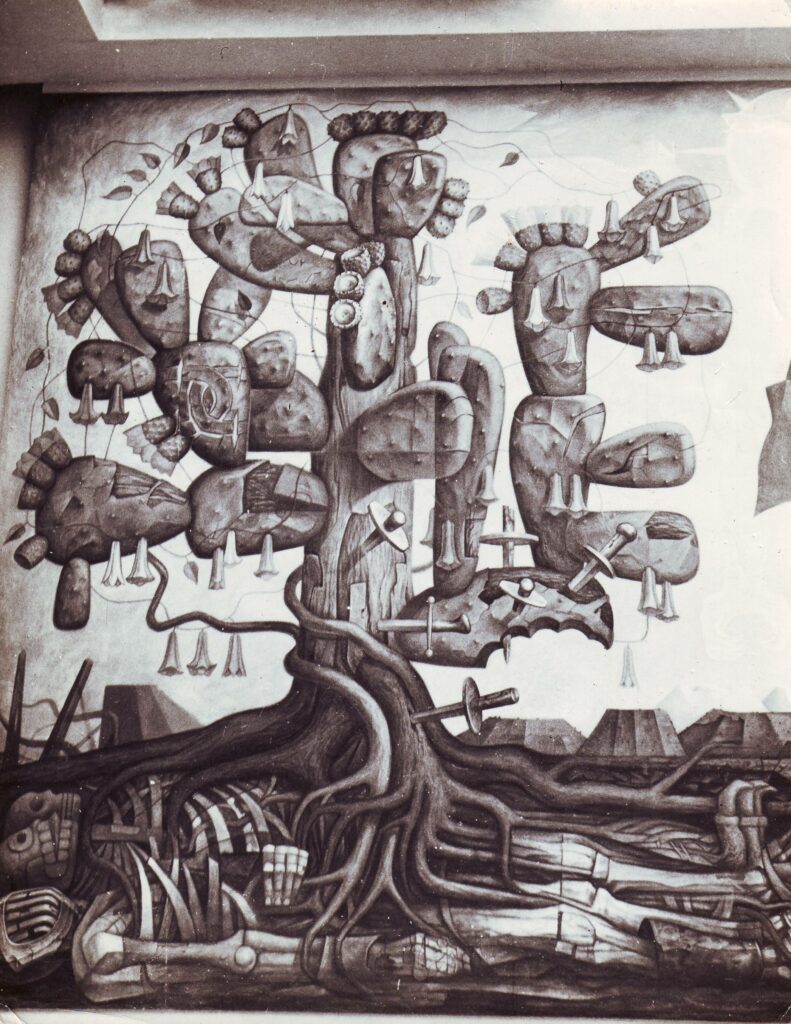

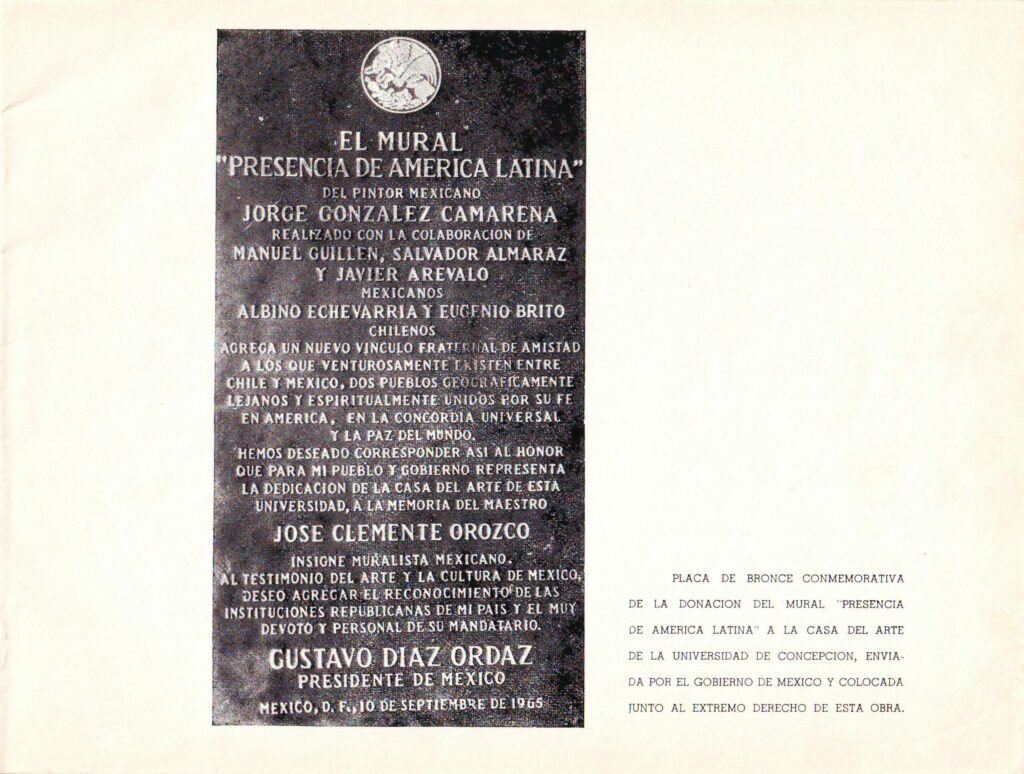

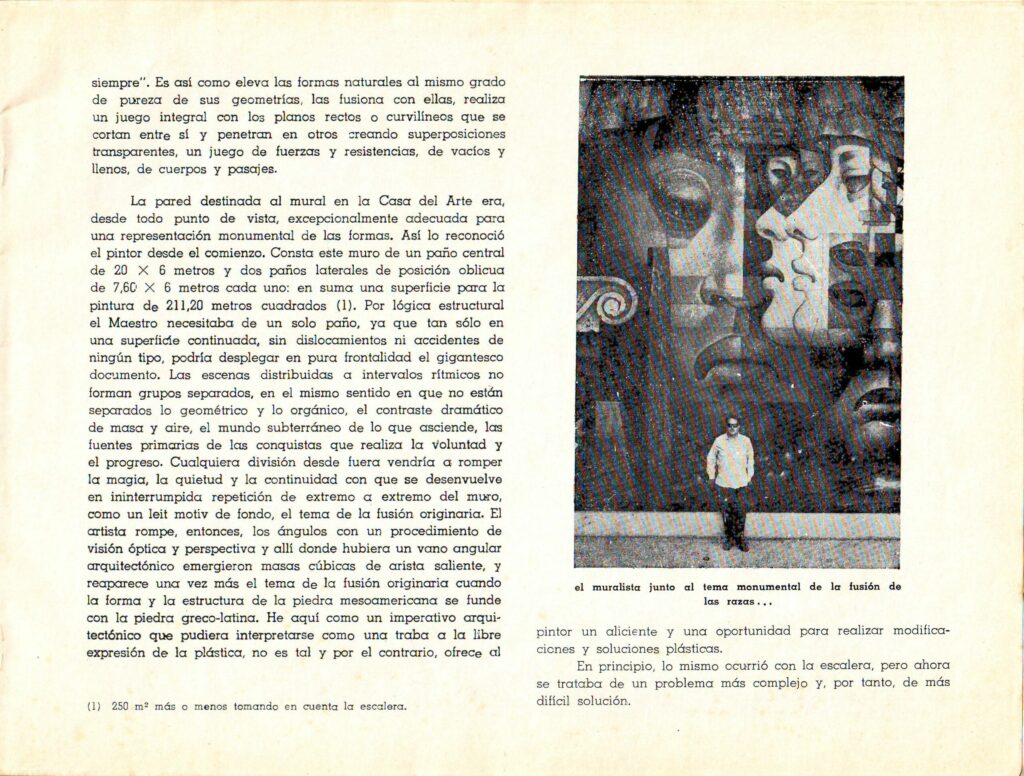

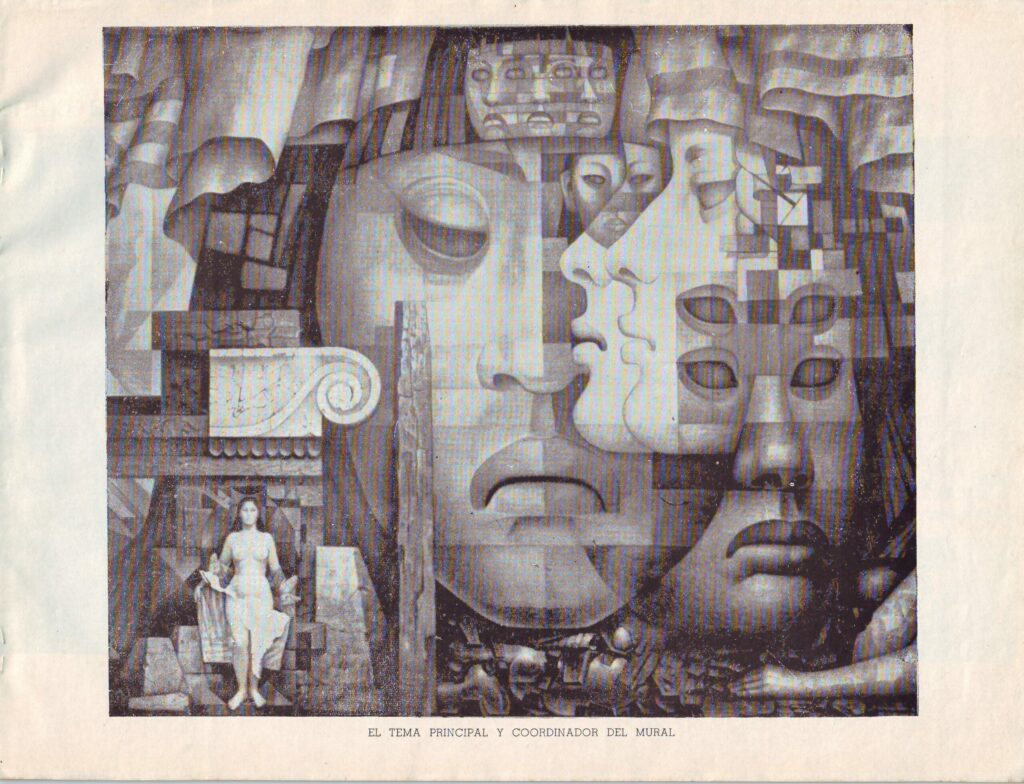

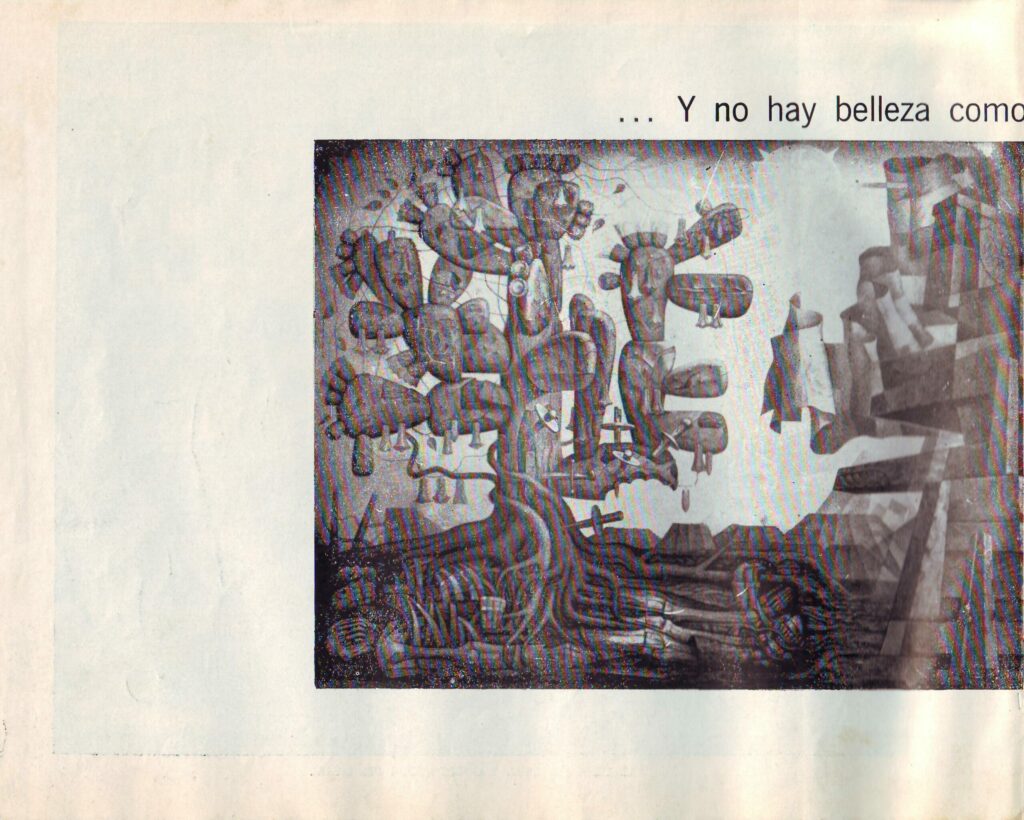

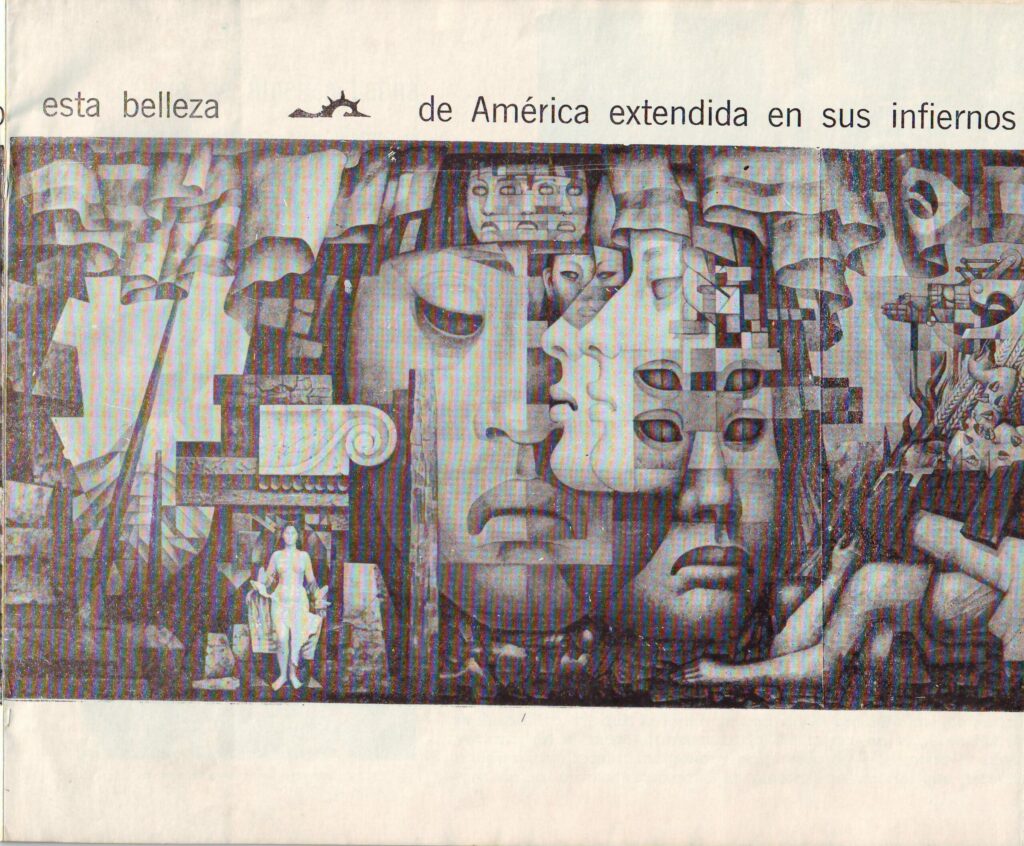

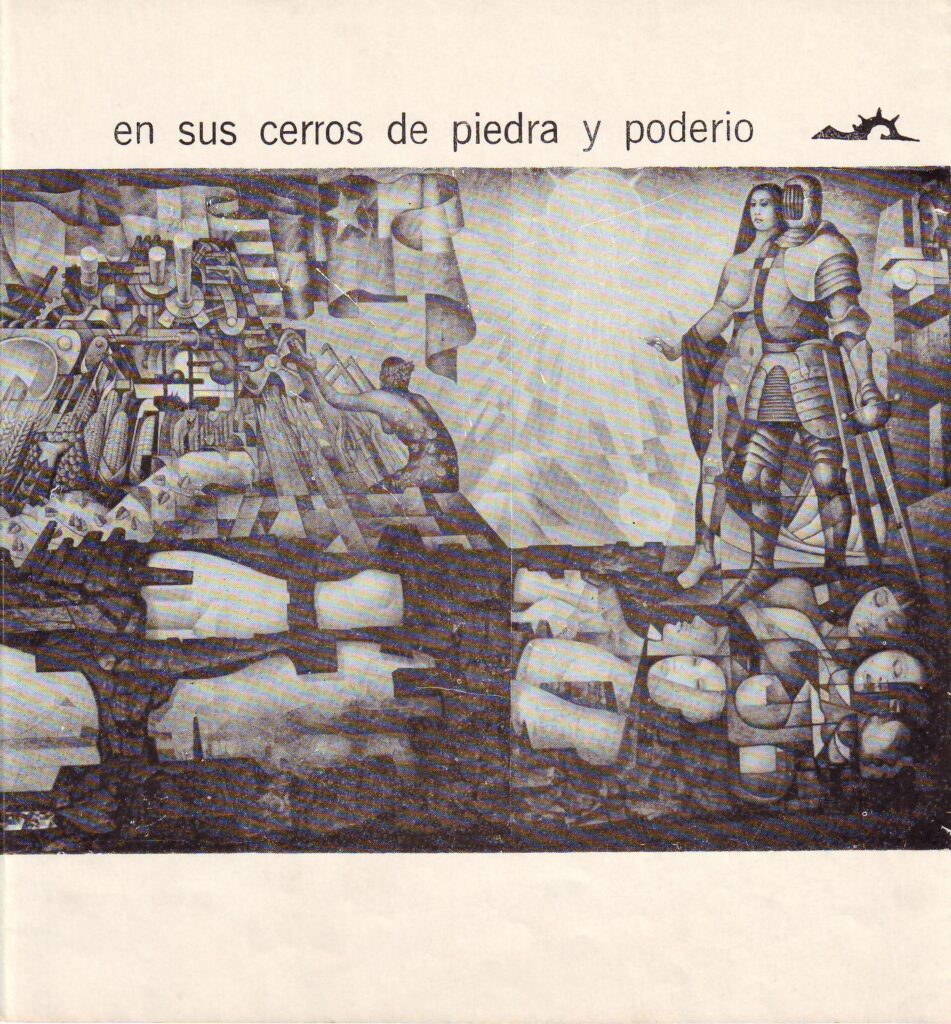

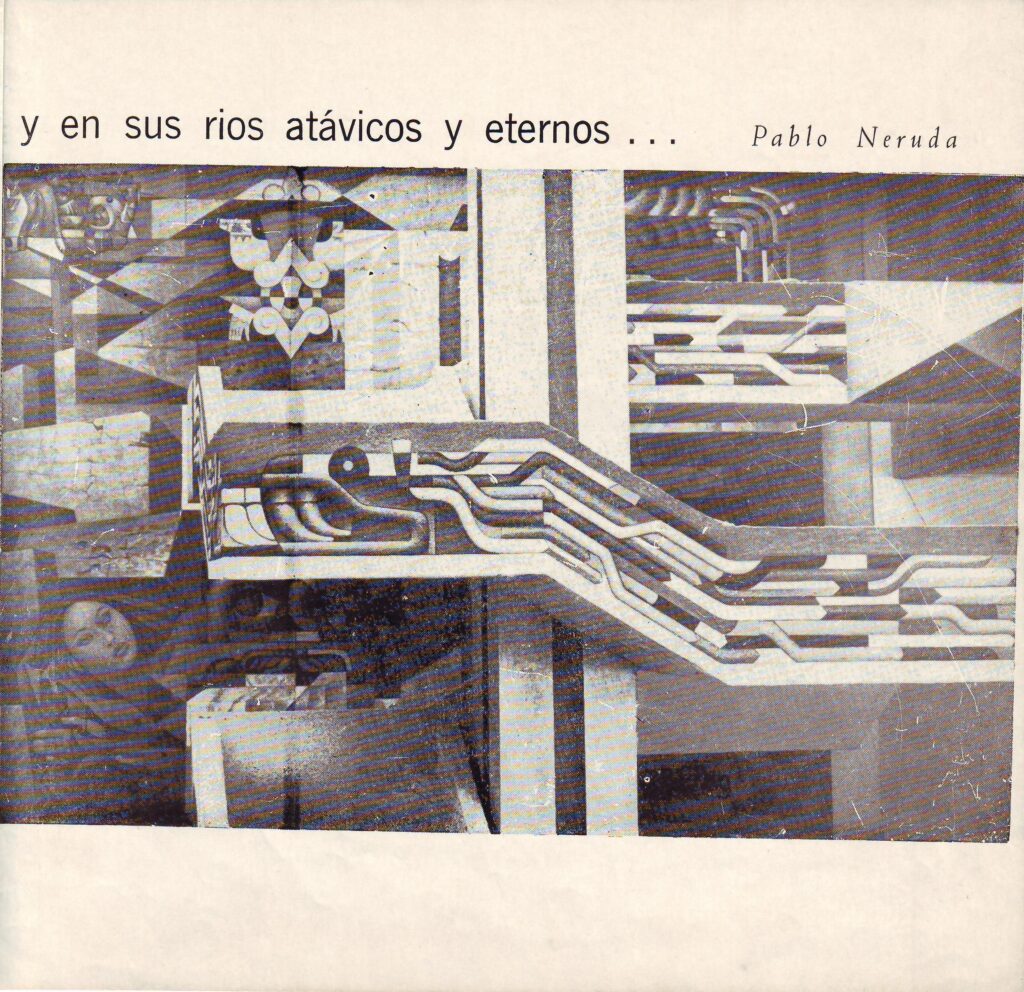

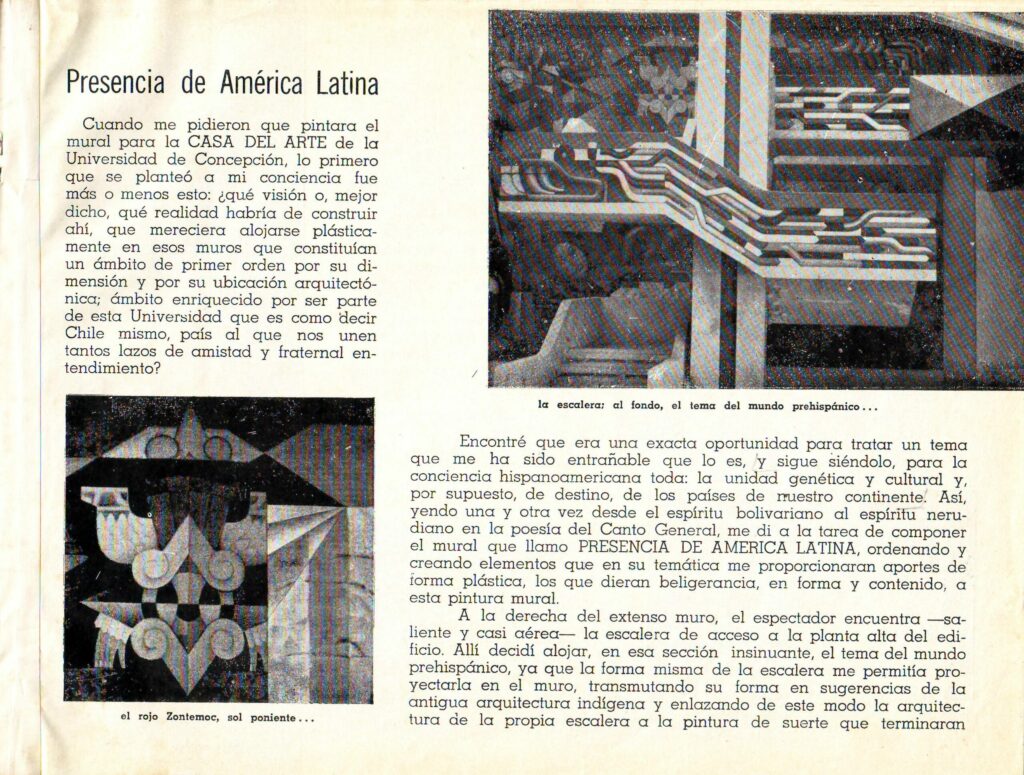

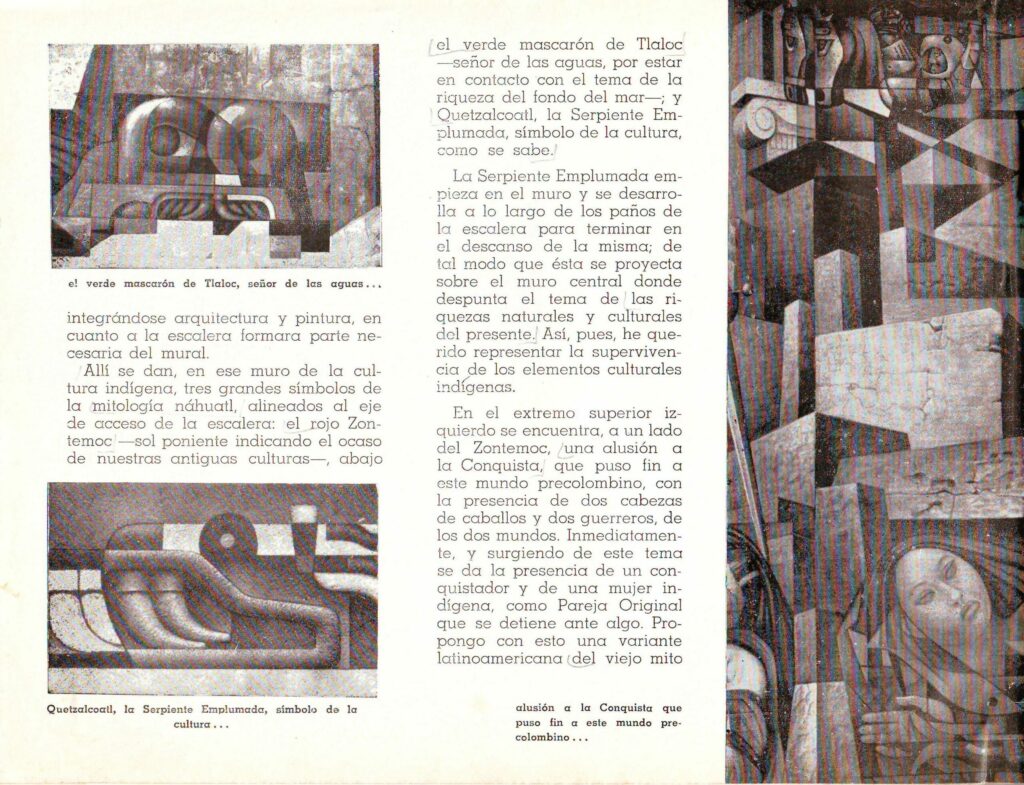

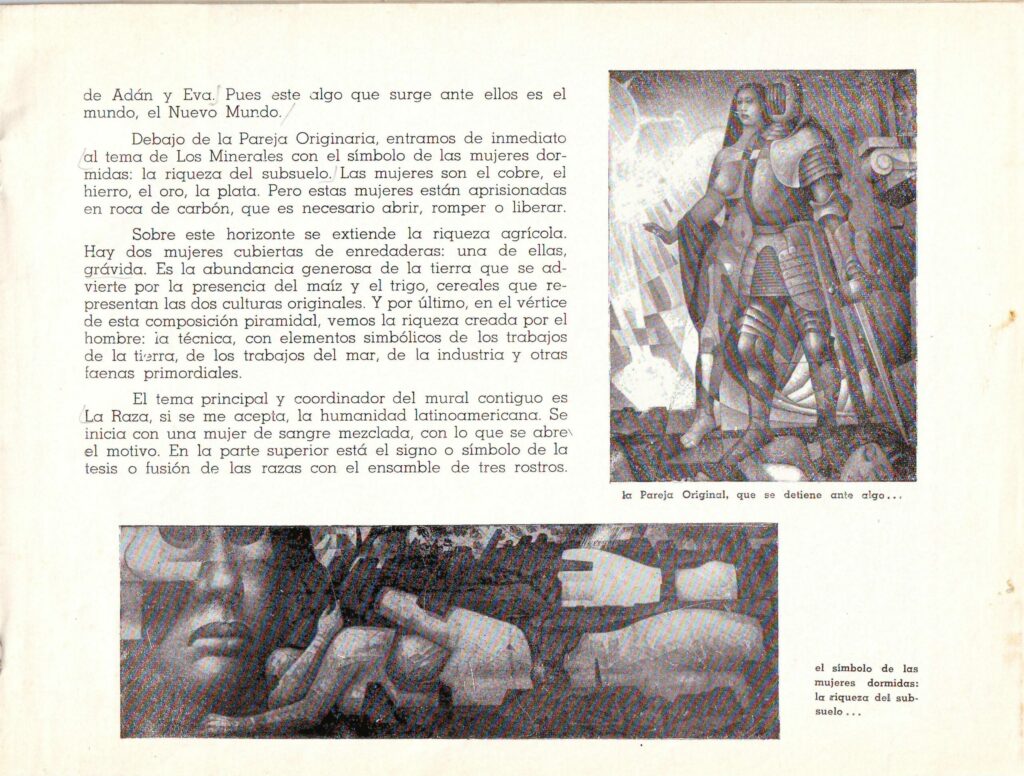

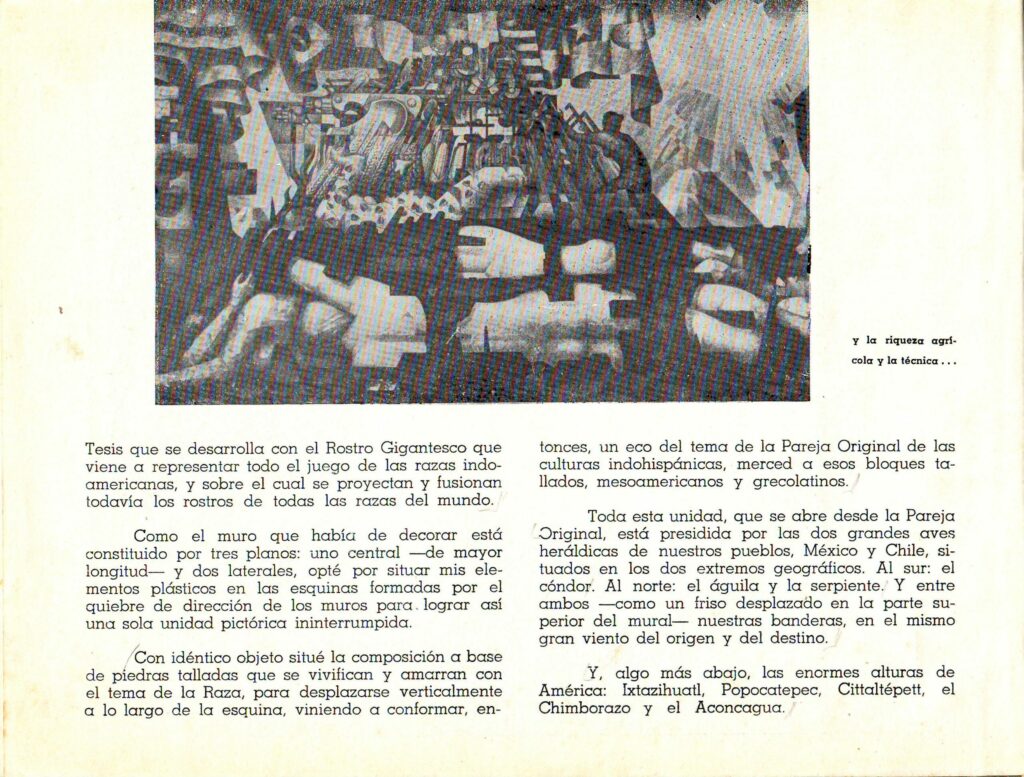

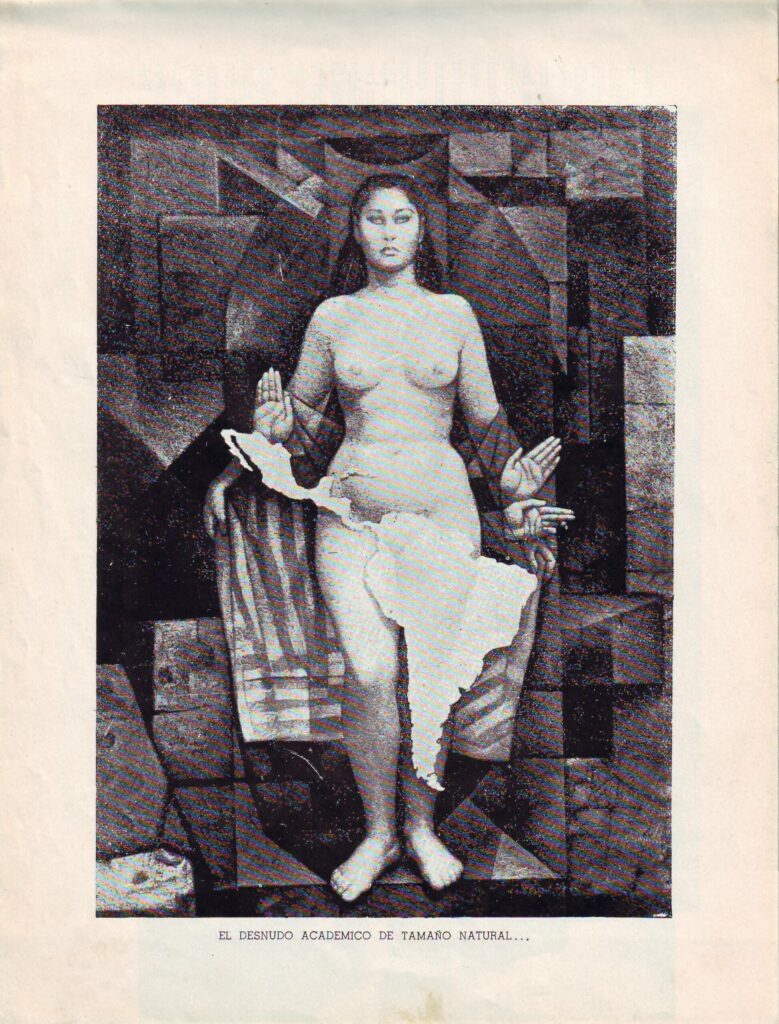

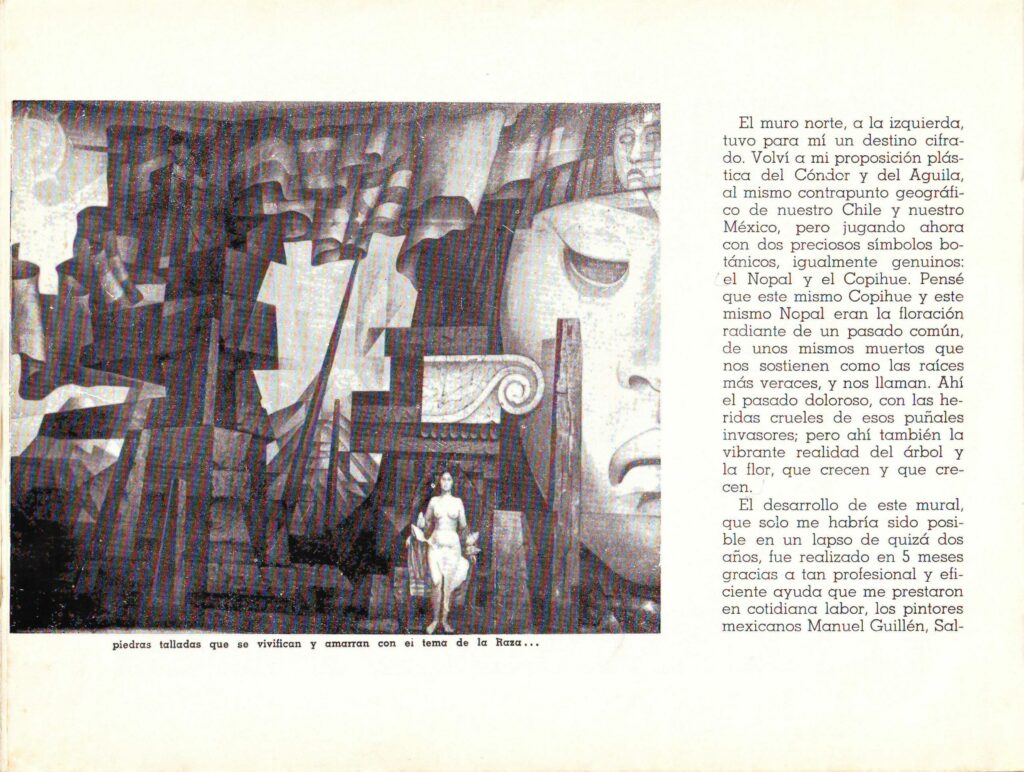

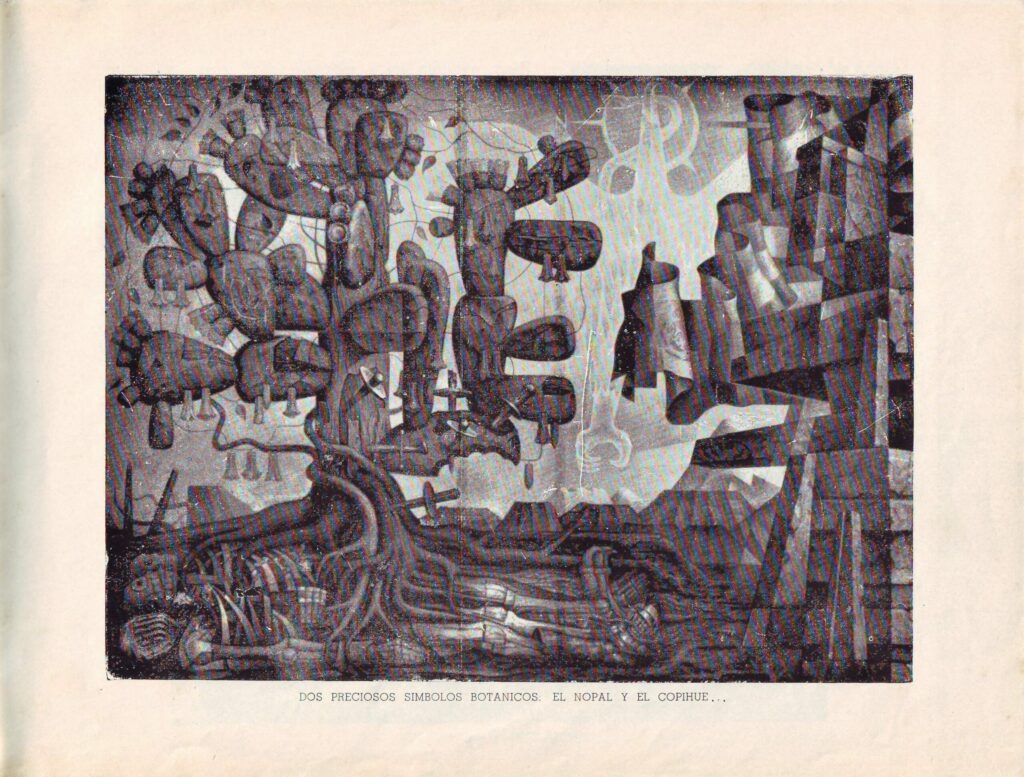

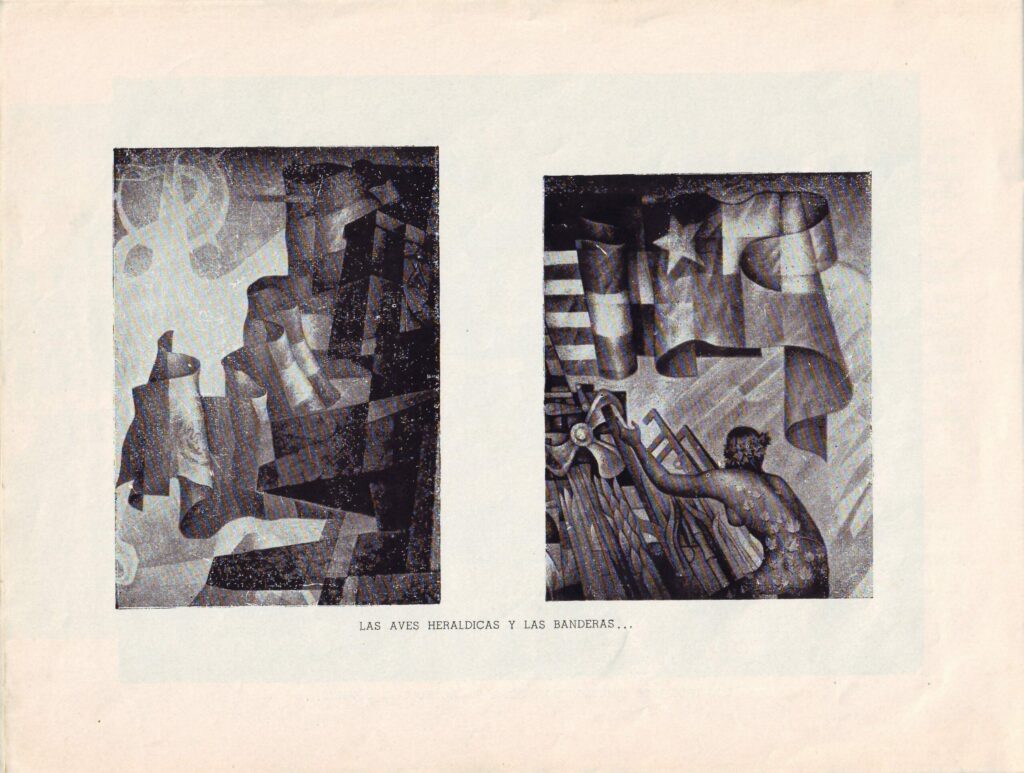

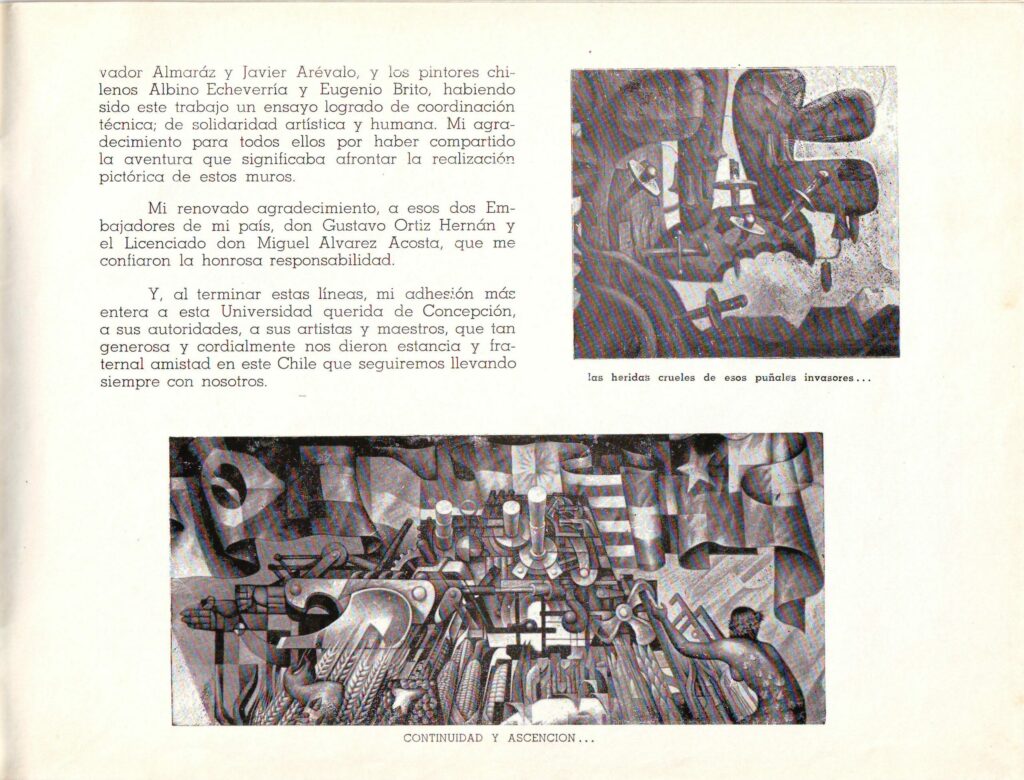

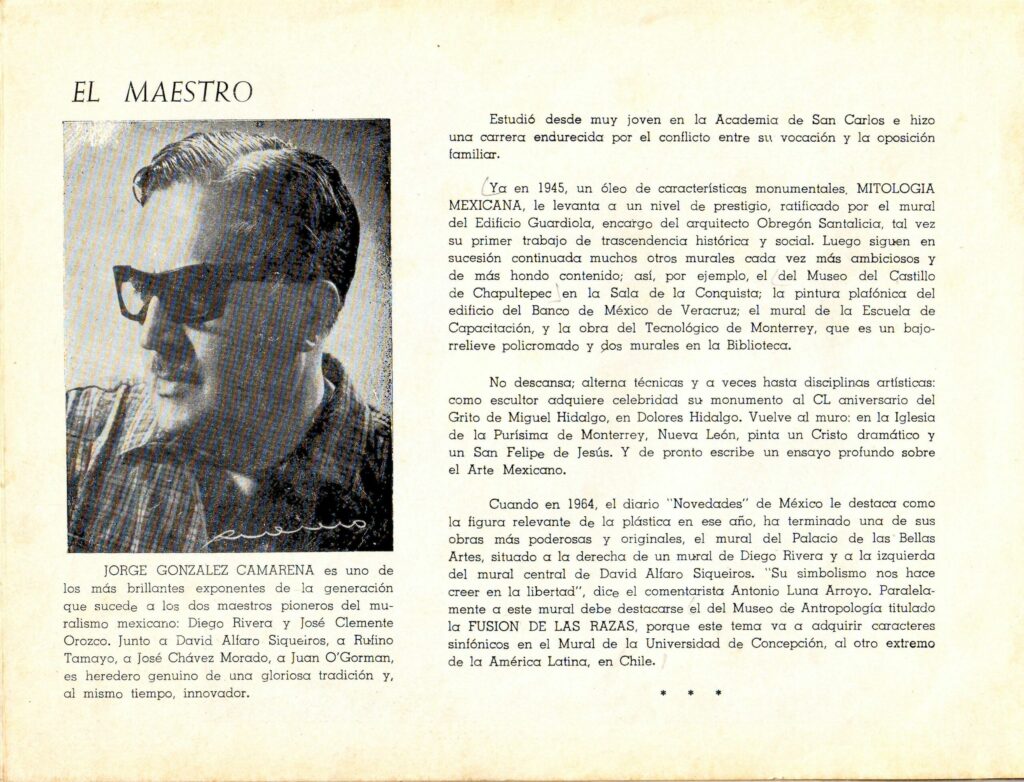

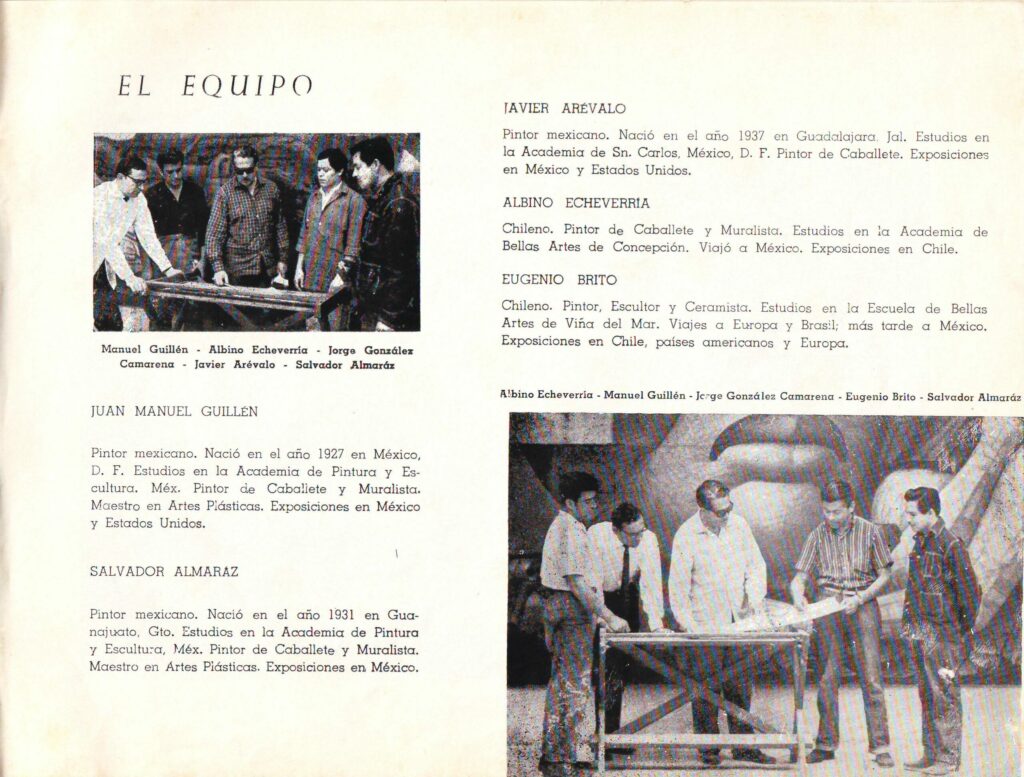

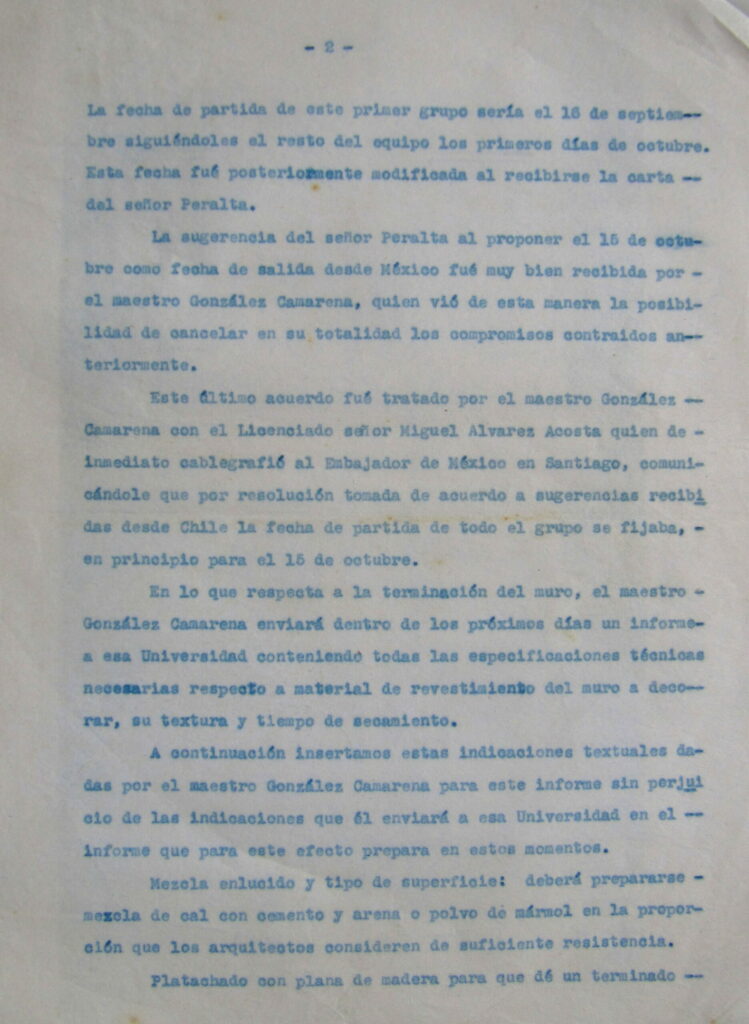

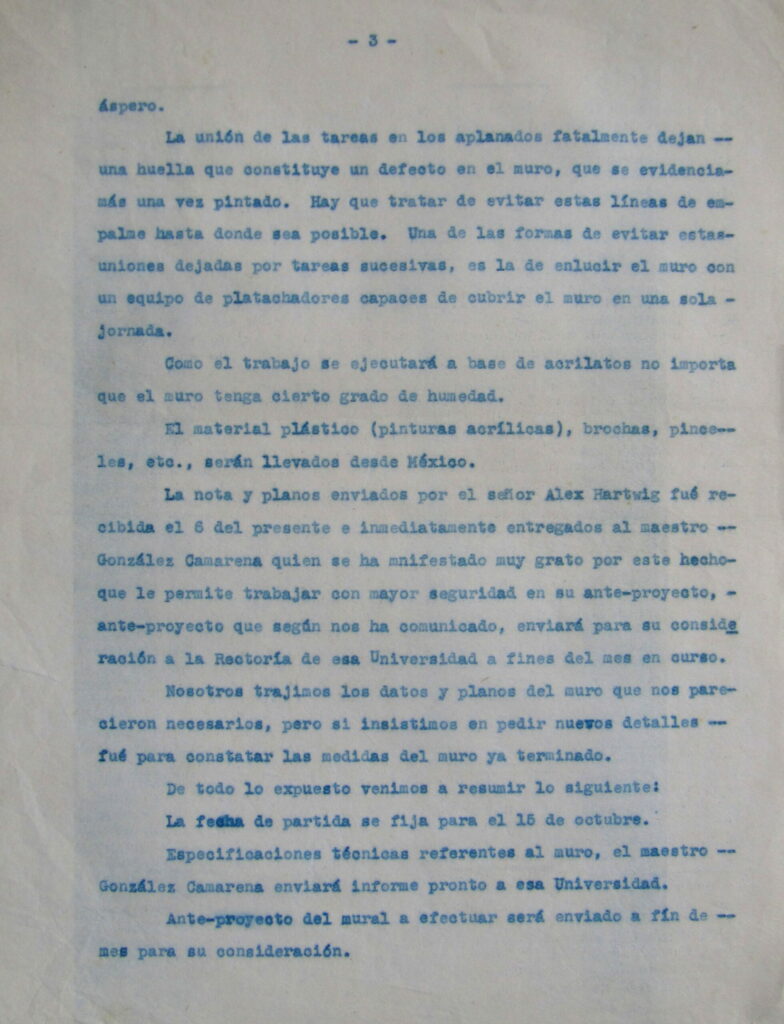

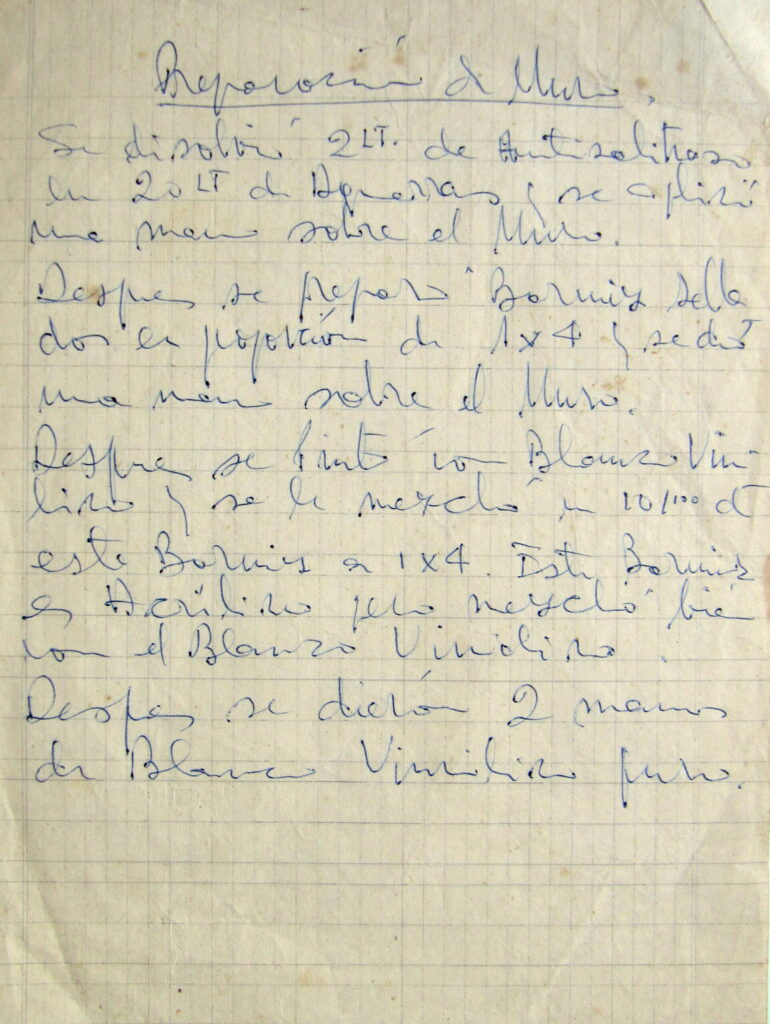

Although a significant portion of the built infrastructure was finished and operational by the conclusion of the Cooperation Plan, the murals remained unfinished due to the necessity of constructing and preparing the walls specifically for their placement. Artists Mara Matner, Juan O’Gorman, and Roser Bru were commissioned to create the unique murals. This commission also included Jorge González Camarena and his team, who painted the mural ‘Presence of Latin America’ on the interior wall of the ‘José Clemente Orozco’ House of Art at the University of Concepción. The mural was conceptualized and designed specifically for this purpose. The architectural project by Alejandro Rodriguez and Osvaldo Cáceres started in 1963 and concluded in 1965.

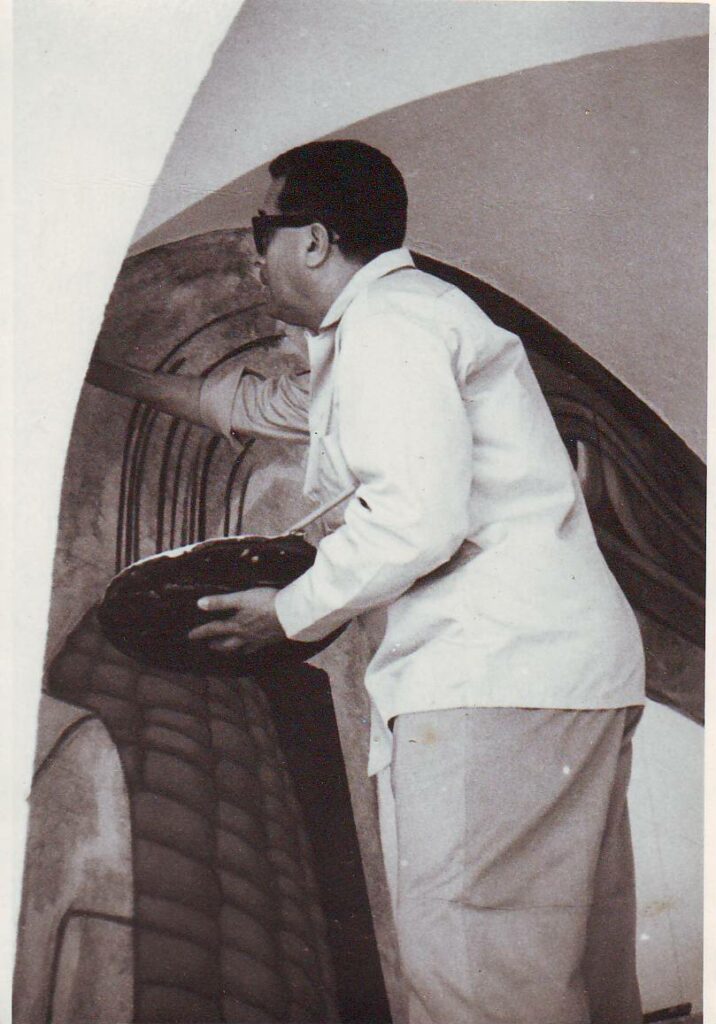

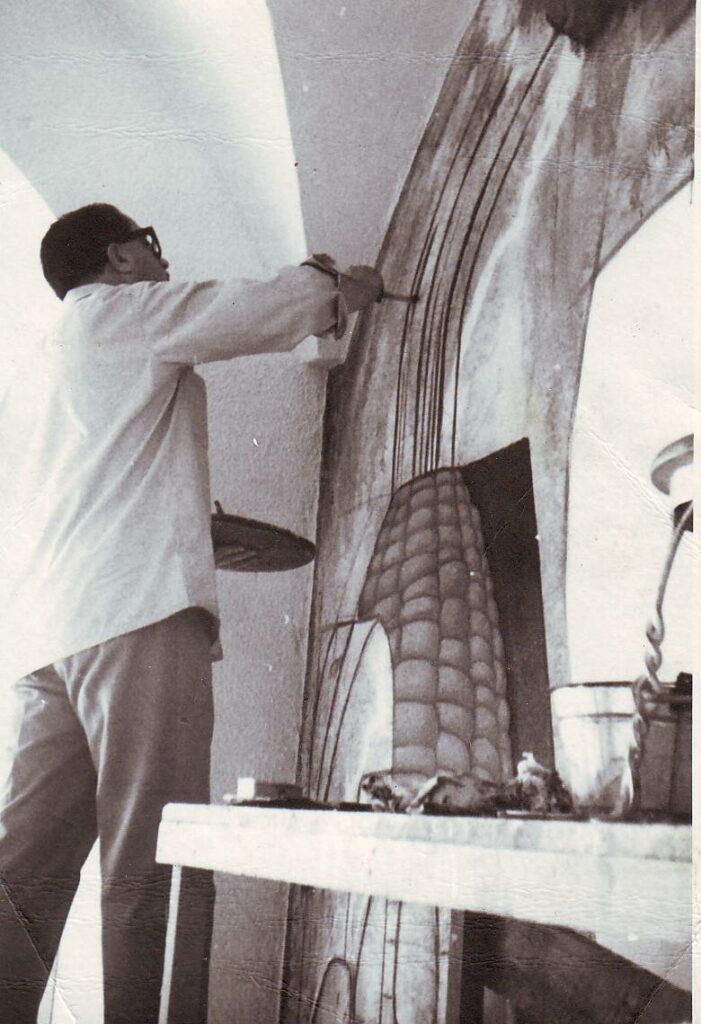

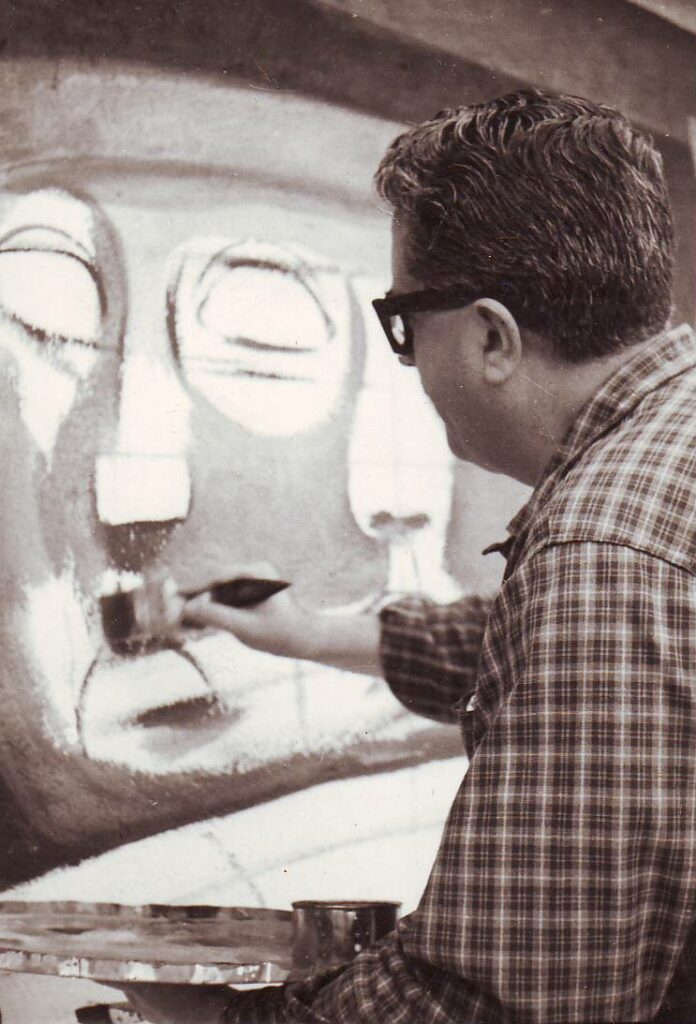

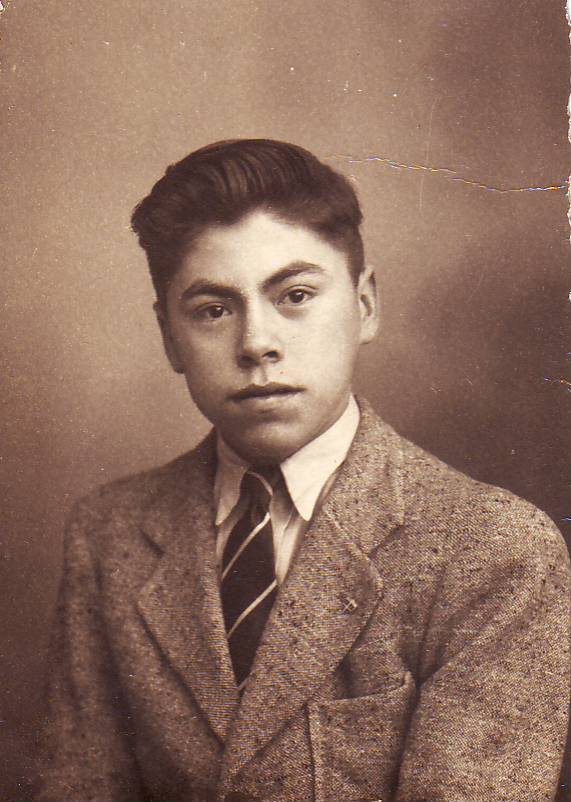

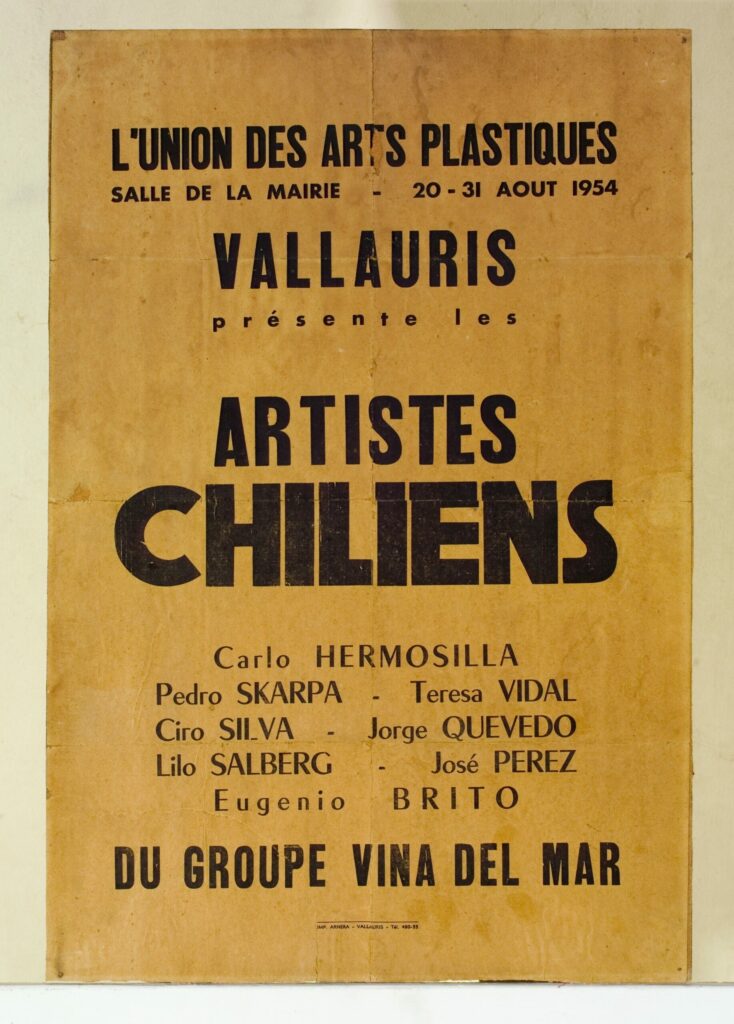

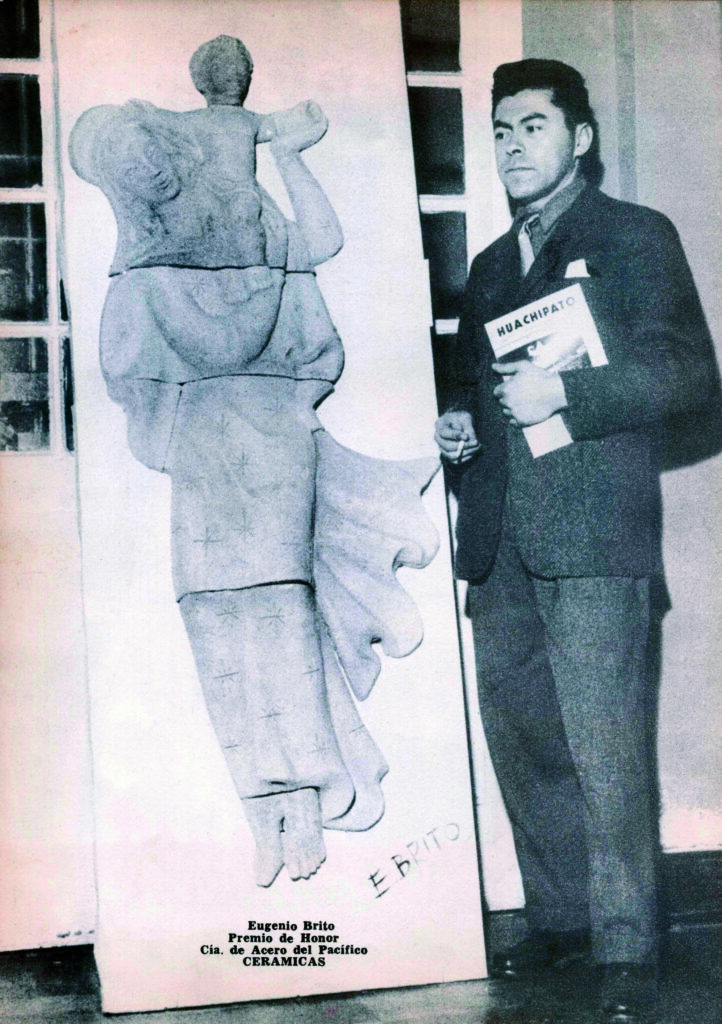

Eugenio Brito Honorato participates in this last mural as one of the collaborators of the Master Jorge González Camarena.

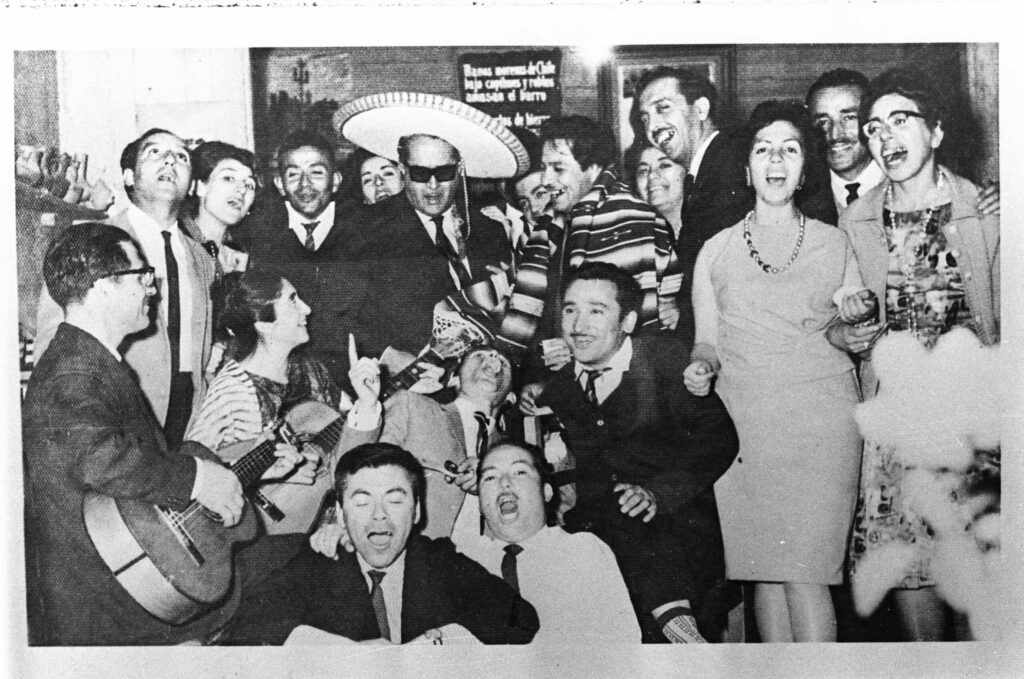

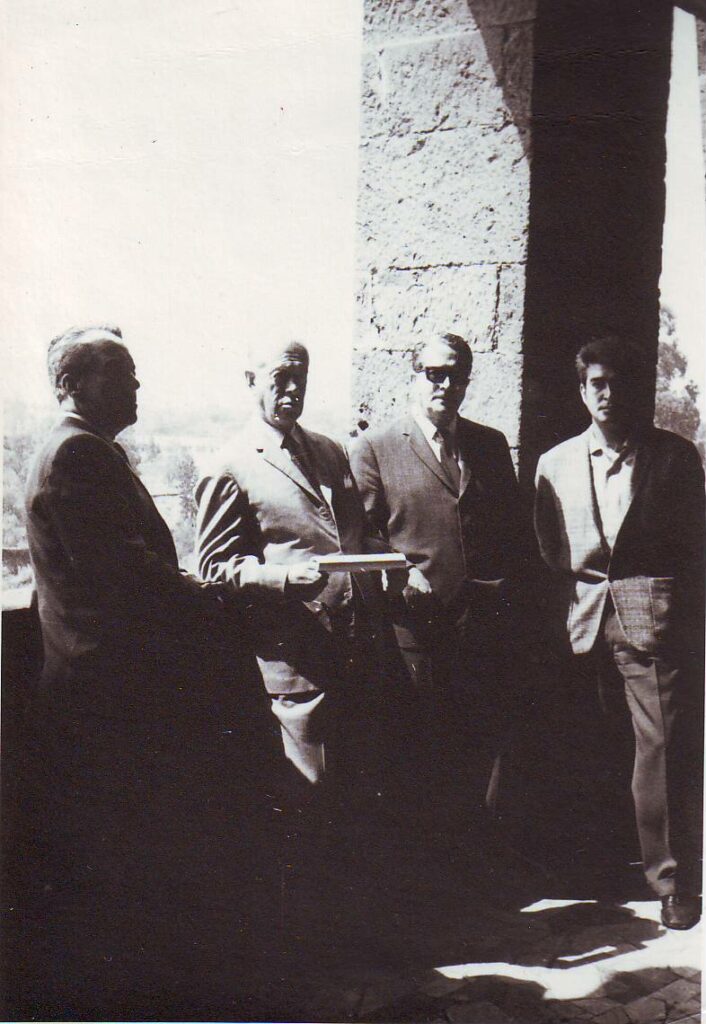

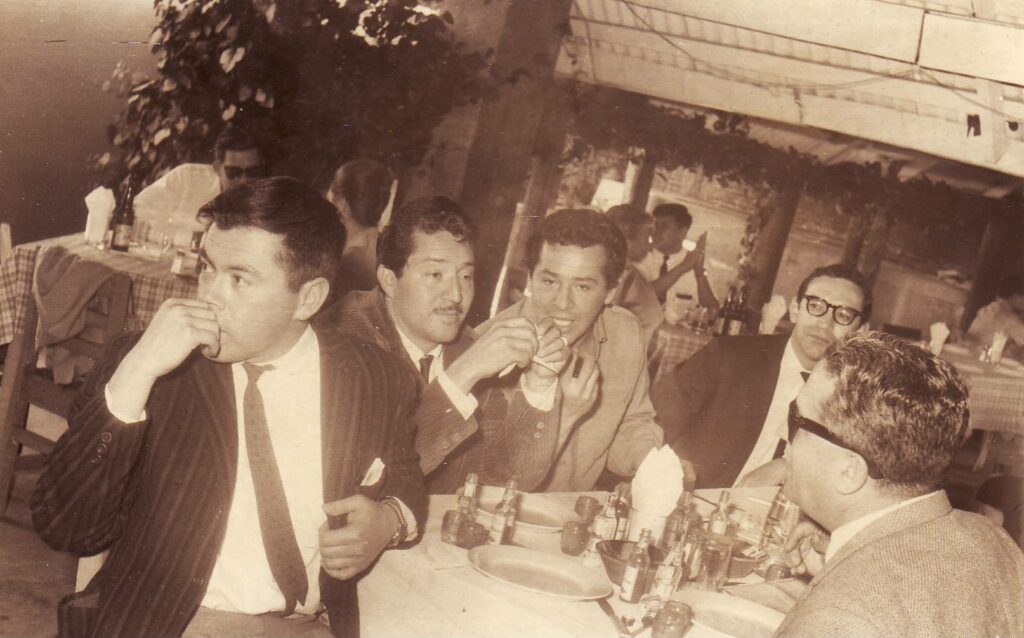

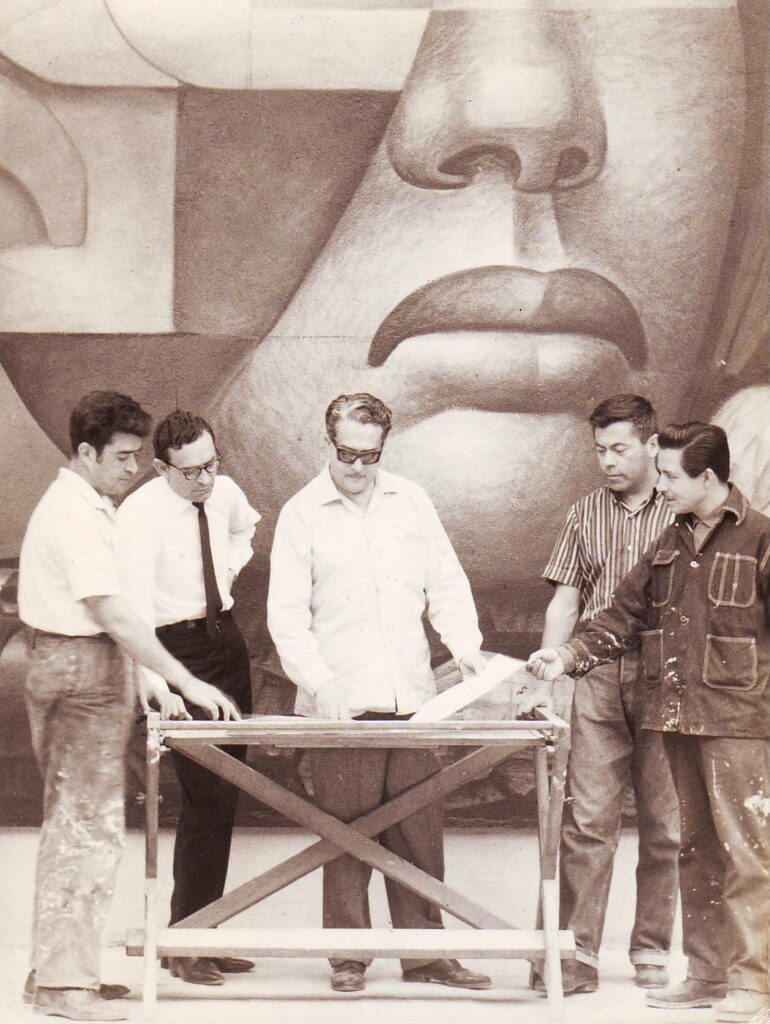

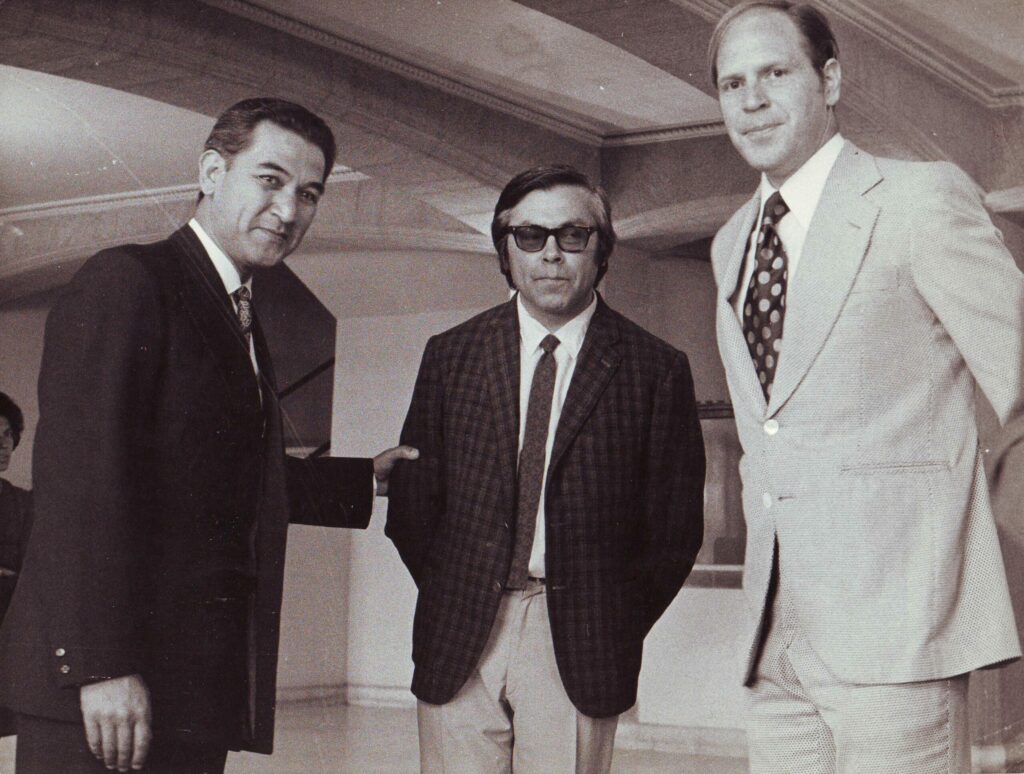

Meeting with Master Jorge González Camarena.

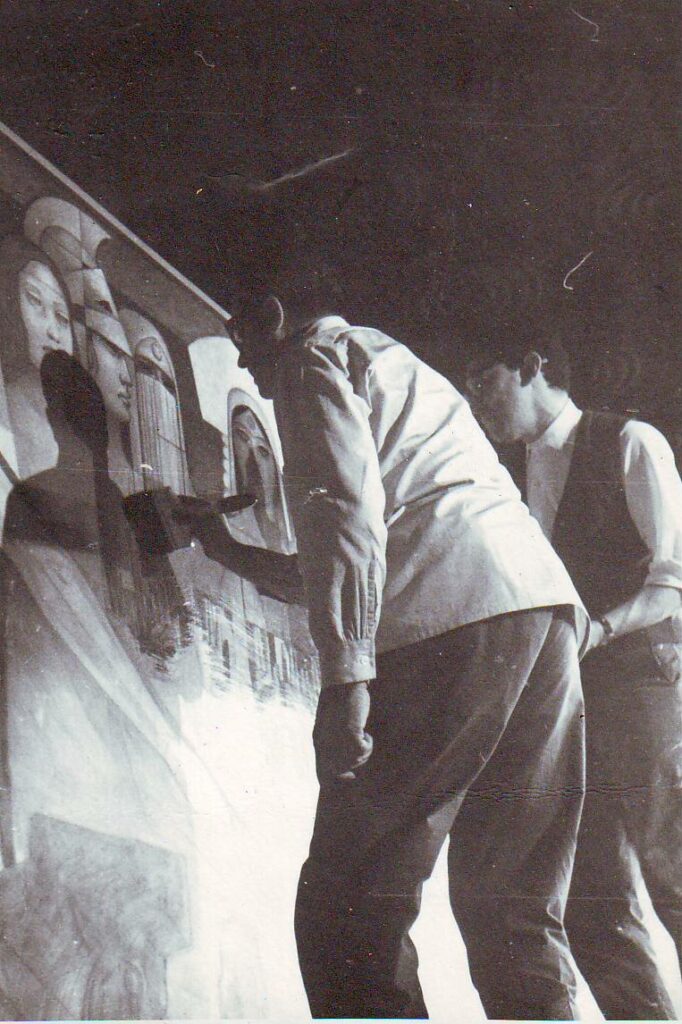

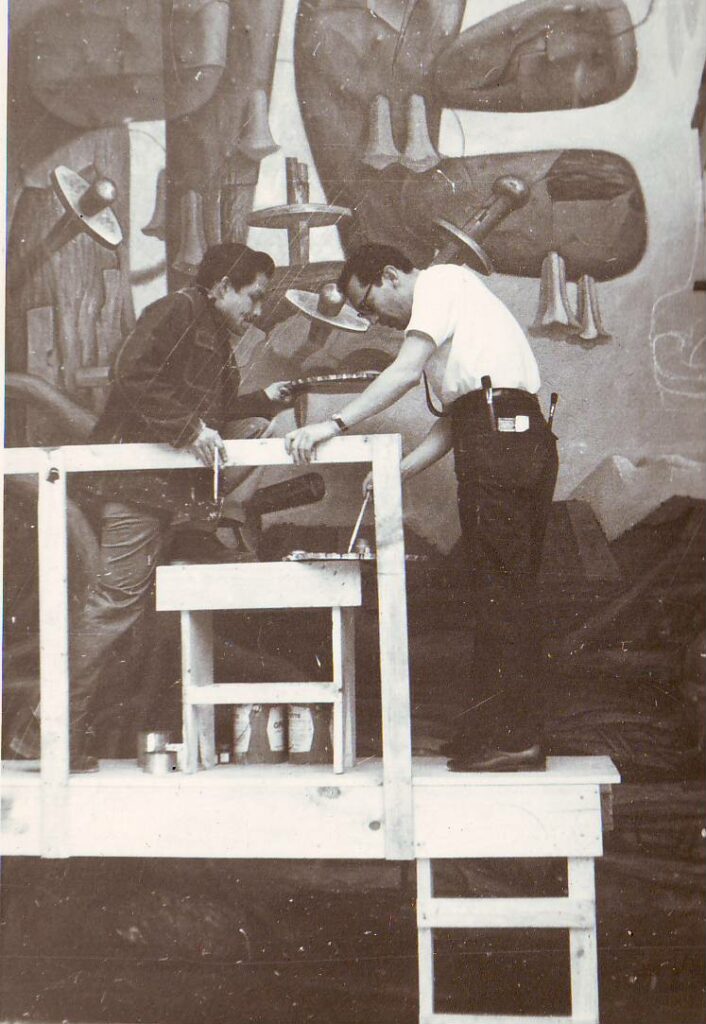

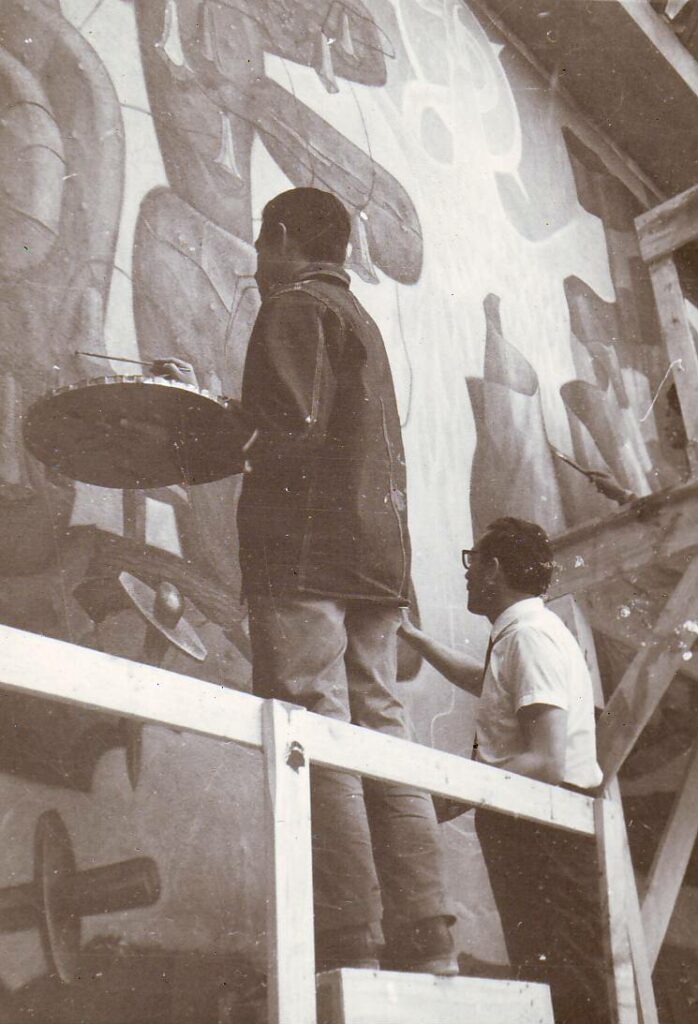

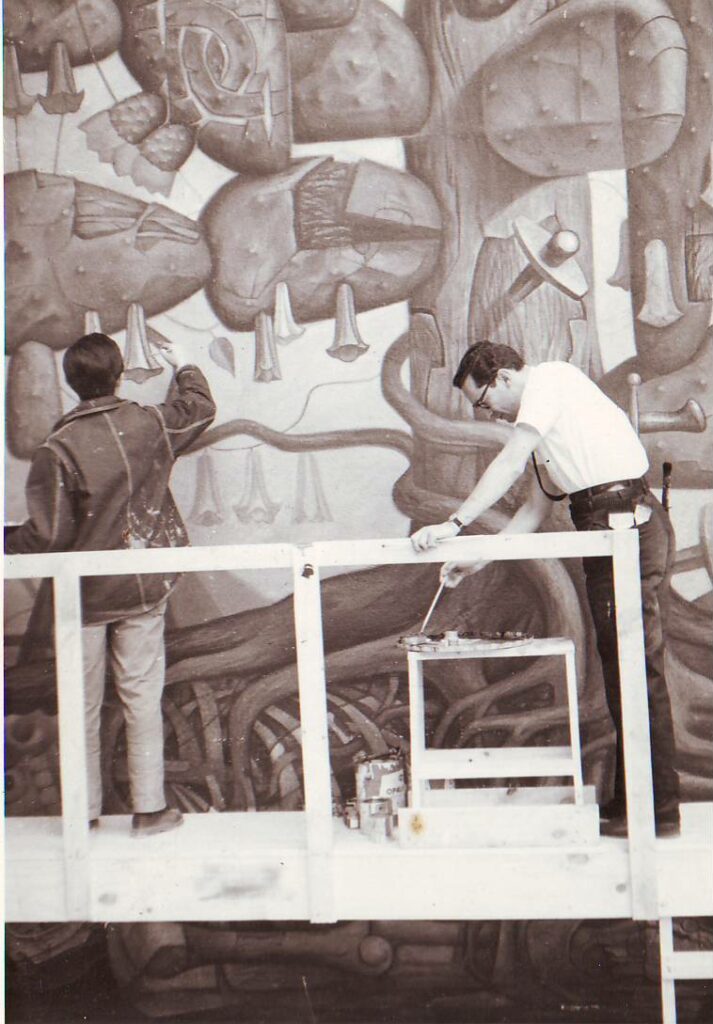

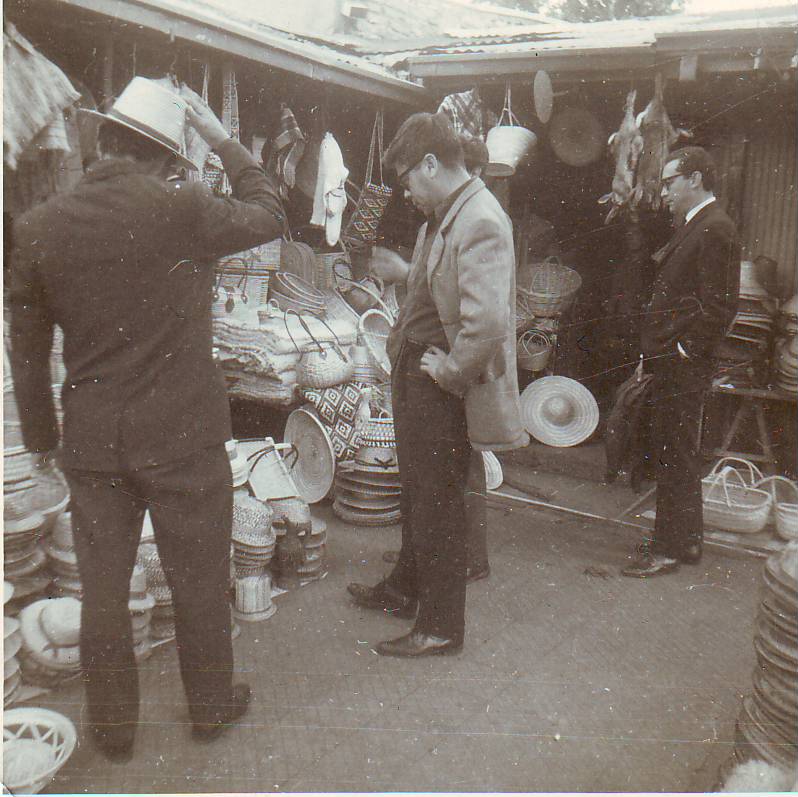

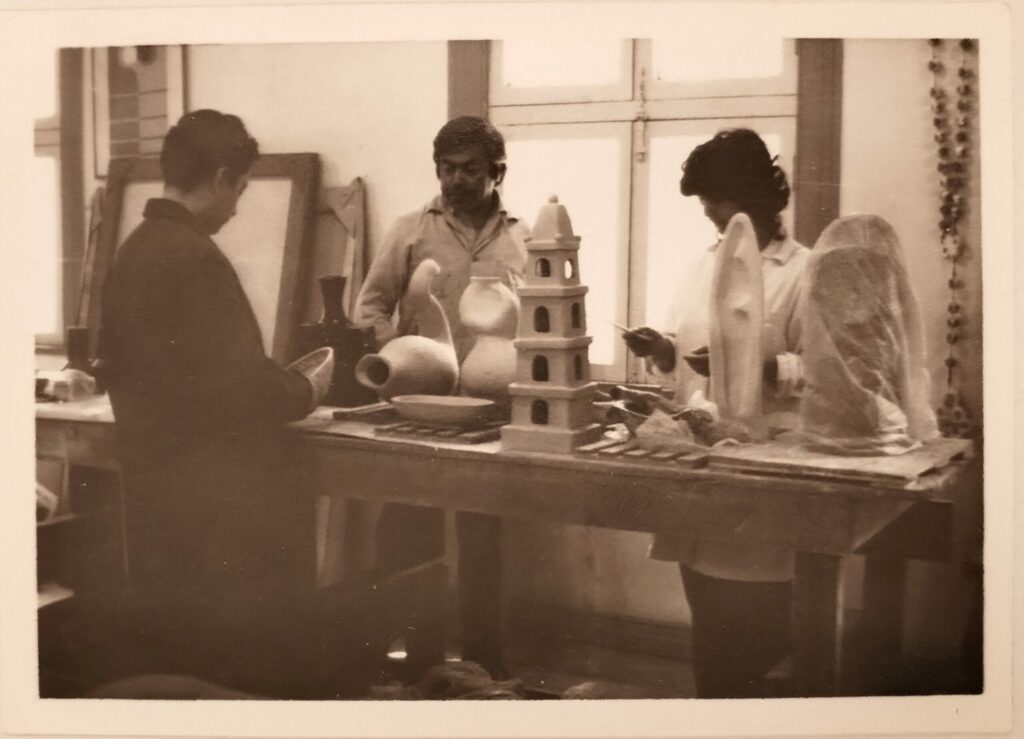

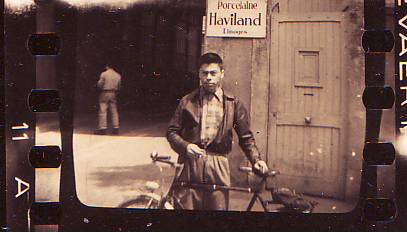

In accordance with the Chilean-Mexican Cooperation Plan, the OPIC, the Organization for the International Promotion of Culture of the Mexican Foreign Ministry, which oversaw all activities conducted in Chile during the aforementioned Cooperation Plan, extends invitations to the artists Albino Echeverría and Eugenio Brito Honorato. These artists traveled to Mexico with the support of the University of Concepción to meet with the professor Jorge González Camarena, collaborate with him on the murals he was creating, and learn about his techniques and concepts. (Photographs 1, 2, and 3)

In Mexico, the mural “Races” was crafted in this manner, and it is situated in the Introduction to Anthropology room of the Anthropology Museum of Chapultepec. Additionally, they painted ‘Coatlicue’ for the Cuernavaca Art Museum. ‘Albino and I were selected by the university to travel on behalf of this house of studies and simultaneously invited by the OPIC, which was in command of all the earthquake-related activities taking place in Chile in the 1960s. Thus, we were able to travel to Mexico and absorb the master’s manner, work with him on murals he was creating in his own country and study his techniques and concepts. We believed we possessed particular knowledge, but this was not the case. I recall that my first endeavor to collaborate on the mural at the Chapultepec Museum of Anthropology was extremely difficult’ (This and the following paragraphs are excerpts from an interview on the Concepción University radio program ‘At the foot of the bell tower’ conducted by librettist and announcer Francisco Miguieles on the 18th anniversary of the mural in 1983.)

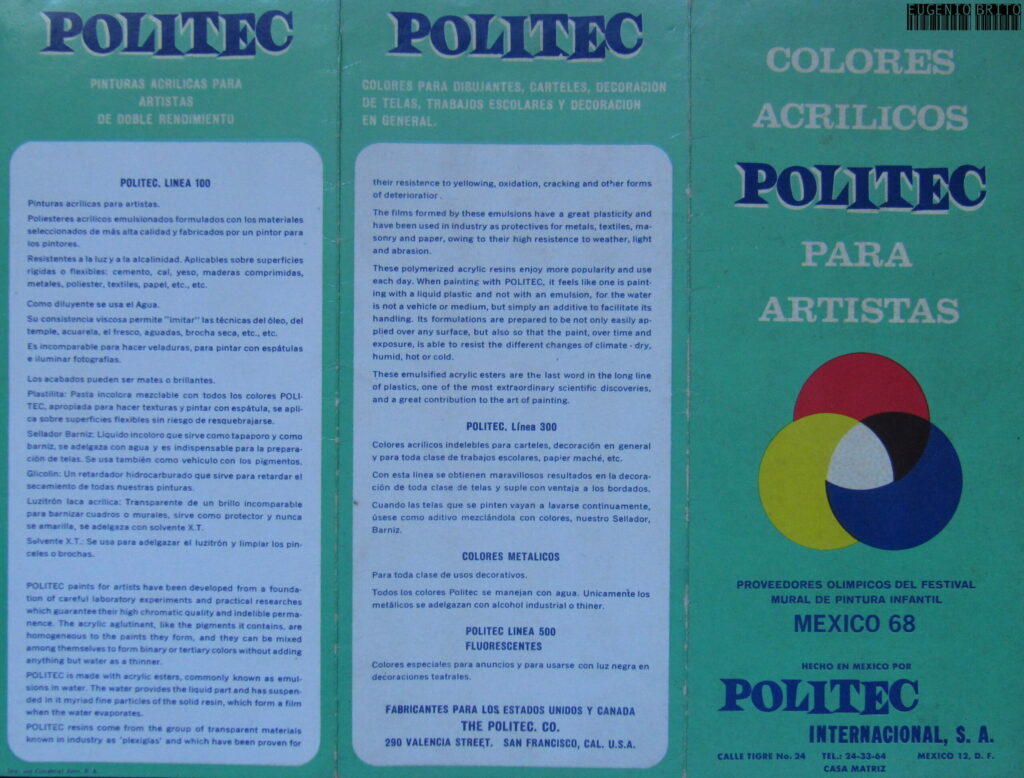

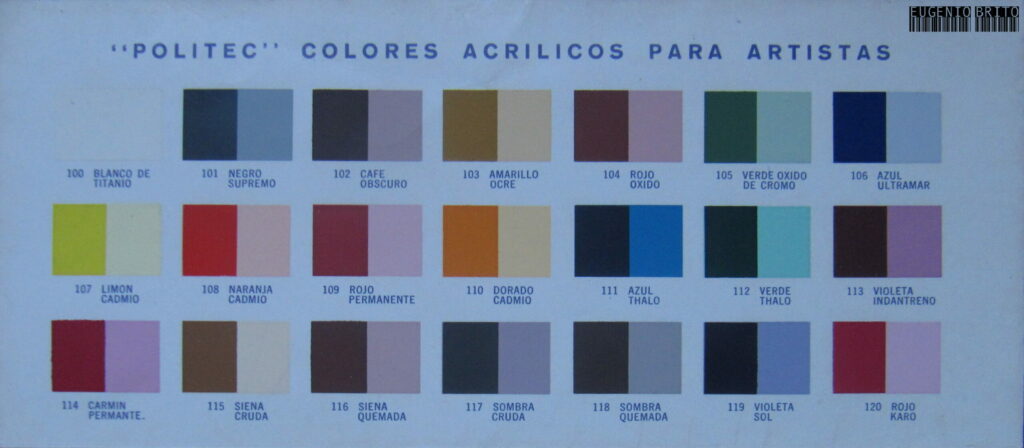

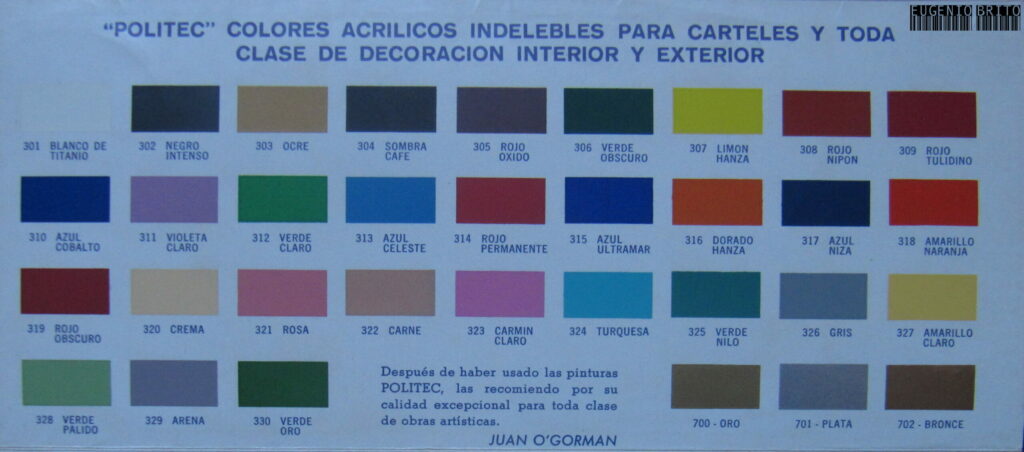

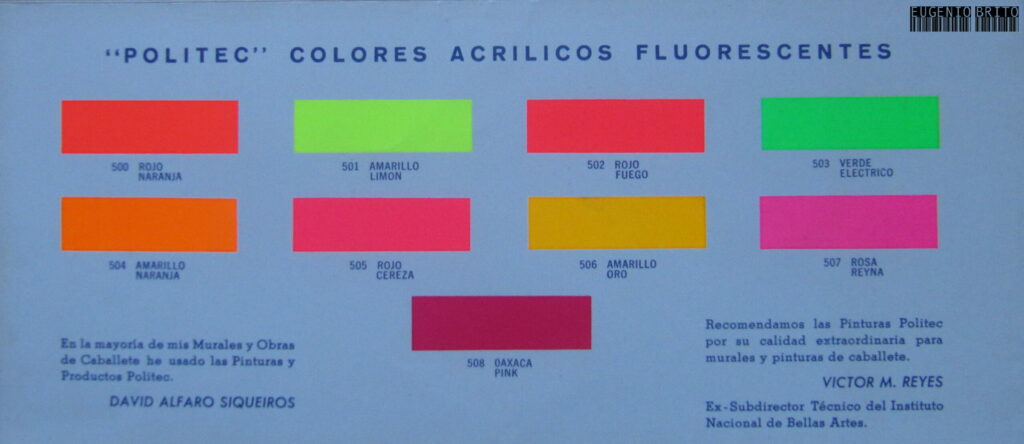

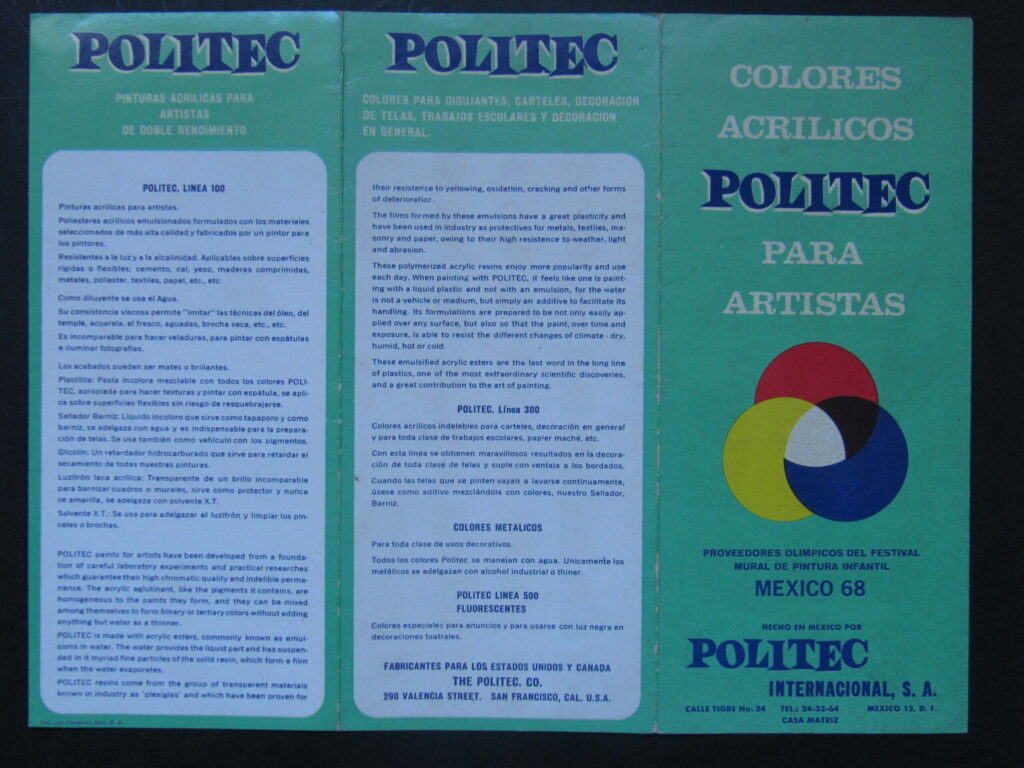

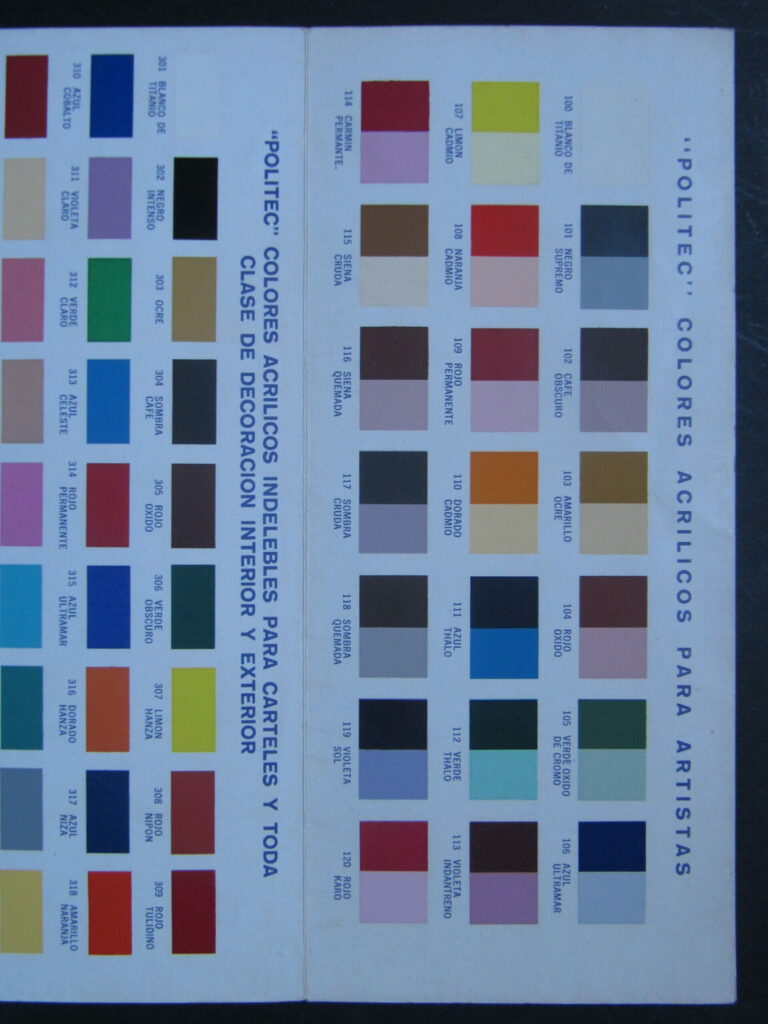

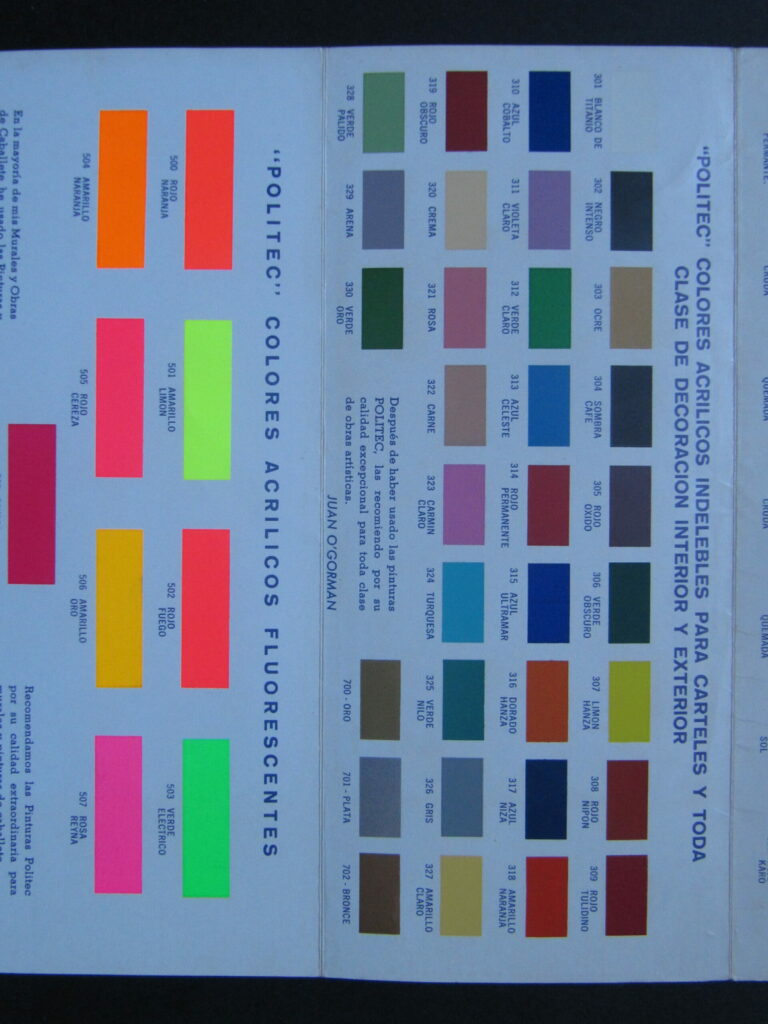

Upon their initial arrival in Mexico, acrylic paintings were also unfamiliar to the two Chilean painters, in addition to the instructor González Camarena. We made use of materials that, by virtue of the mural’s dimensions in Concepción, facilitated a more comprehensive examination and revelation of their capabilities. In reality, they bear striking resemblance to frescoes, although without the technique’s vigor, but with a similar outcome. The pigmentation is standard for all pigments, whereas the plastic vehicle is contemporary, reliable, tried-and-true, and modern. The latter, as this mural has maintained its color throughout its eighteen years of existence, is evidence. This unequivocally demonstrates its resilience and nobility.’