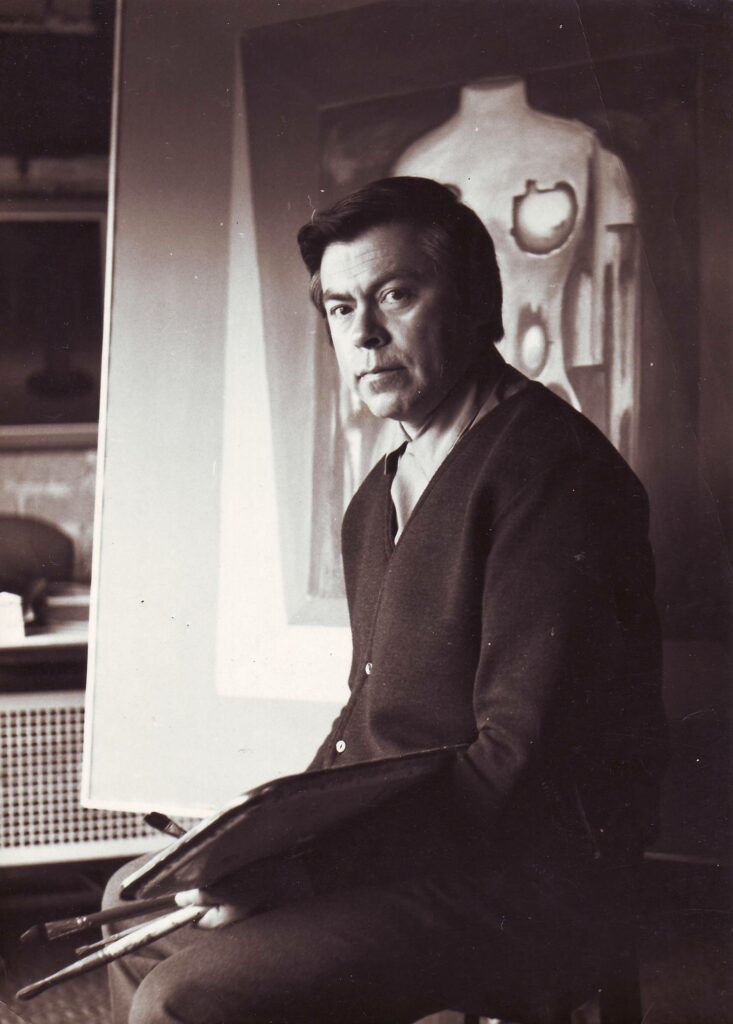

He showed up one morning, reserved and courteous. I spotted him strolling down the long hallway of the school with Enrique Ordóez, saying hello, walking through the workshops, and witnessing our work as students. He moved to Concepción from his hometown of Viña del Mar to become a professor of painting and the director of the Department of Plastic Arts at the University of Concepción. They were difficult times.

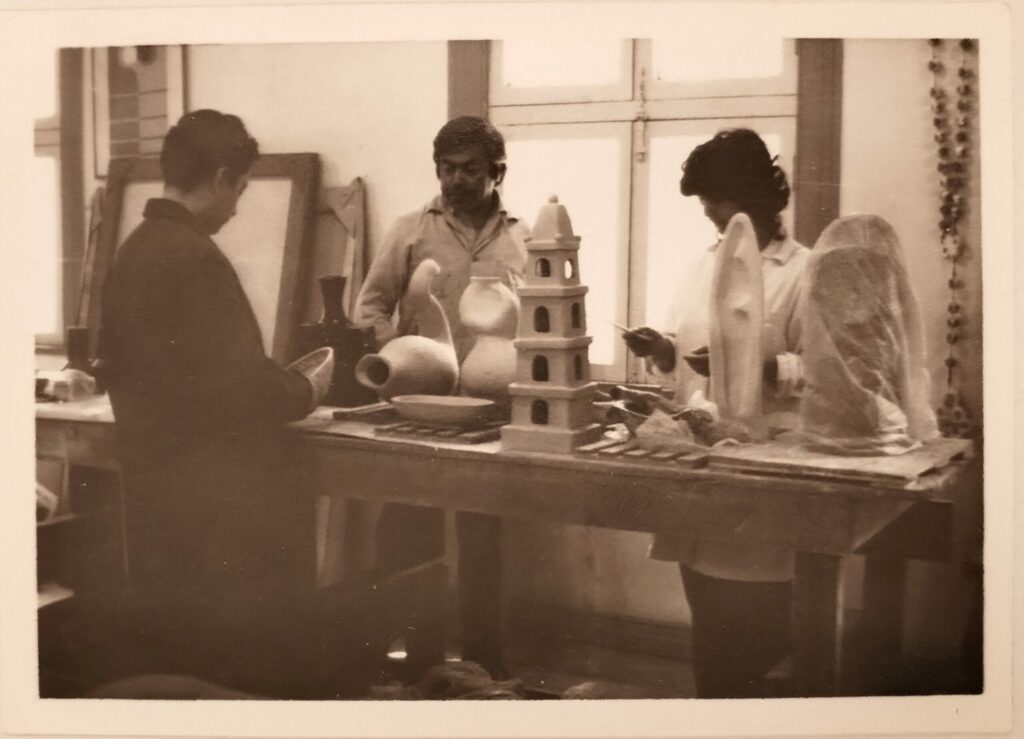

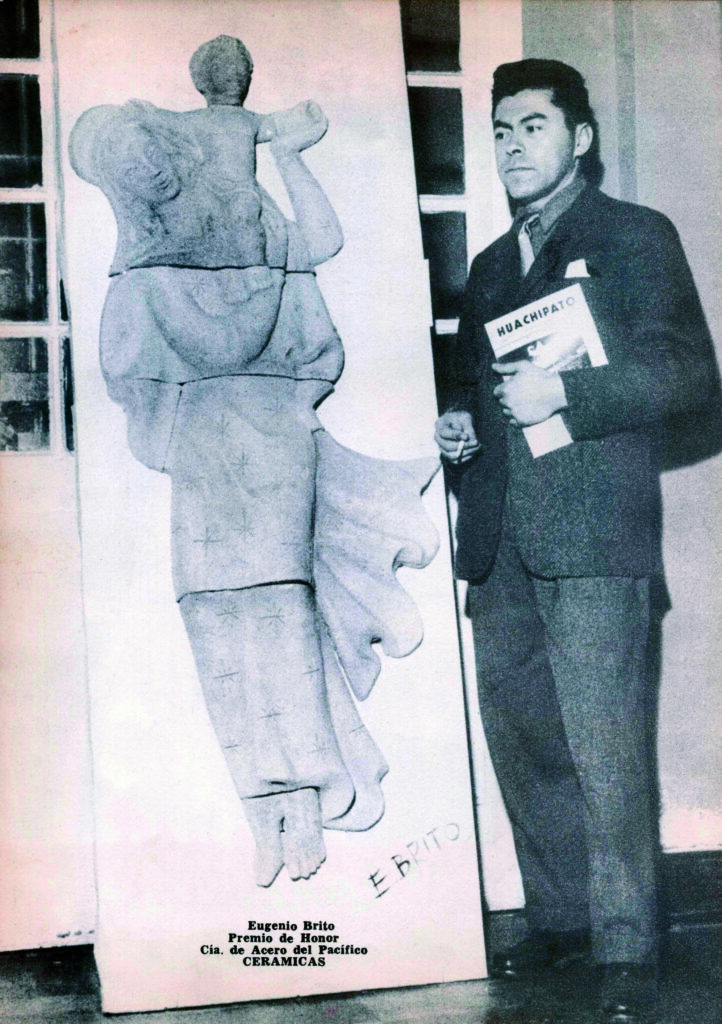

Eugenio Brito, a plastic artist who had established a significant career as a sculptor and ceramist, was getting awards and recognitions as a painter and muralist at the time, which is why I believe he came to teach at our school’s painting program rather than the sculpture workshop, as we would have preferred. He would occasionally visit the sculpture workshop, comment on our work, and get enthusiastic about the technical possibilities that granite and wood afforded. I met him there as an art student with a strong interest in this discipline, particularly modeling in clay, the human figure, patinas, and enamels, techniques he had learned at the Via del Mar School of Fine Arts, Lota’s legendary ceramics, and the La Cascada Studio of Concepción since his first visit to this city in the 1950s and 1960s. An important part of his work from that time period is conserved in our region, such as the Las Tres Pascualas mural, built of mosaic and enameled ceramic, on one of the university shopping corridor stairs.

As a result, Brito returned to live in Concepción in 1975, a city he would never leave again. It was a terrible moment in Chile, as it was throughout the country. The entry of the military regime in 1973 had a profound impact not only on national concerns but also on cultural activities. The absence, forced or voluntary, of some of the university’s teachers and more than one student created a sense of precariousness in the Department of Plastic Arts. With the training of new generations of artists, the Bachelor of Arts degree defied suspicion by emphasizing academic drawing, color theory, and sculptural methods, particularly stonemasonry. Academicism acted as a catalyst in our education, such that we moved through sculpture, painting, or engraving without substantial questions (at least the confessed ones), absorbed in the search for our own plastic language, focused on the object, and relied more on the “retinal effect” than in the substance, the critical sense, or the social commitment. Ours was a static visual narrative, divorced from the setting and Chile’s socioeconomic and political concerns at that moment, convulsed, and effectively barred from international art circuits.

Eugenio Brito joins our university instruction in this scenario, bringing his experience as an artist and as a scholarship recipient with residences outside of Chile.

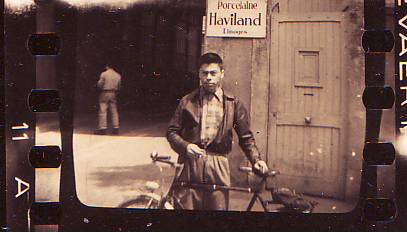

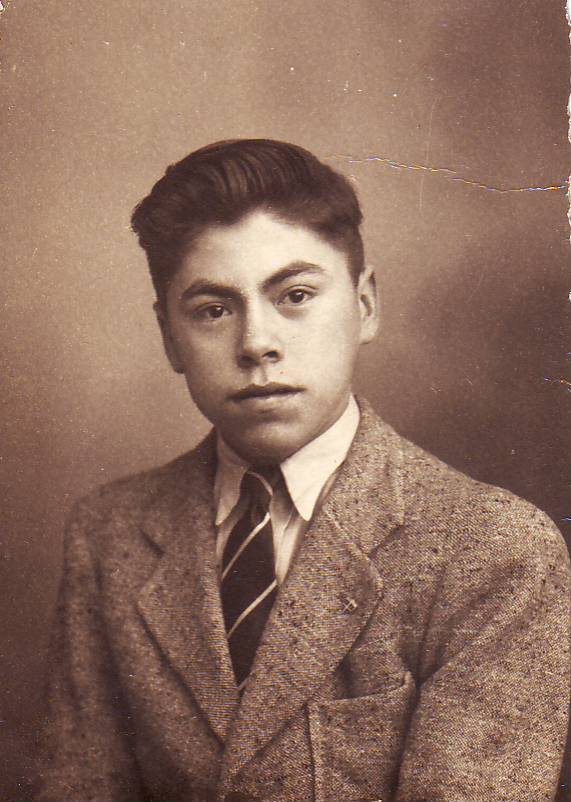

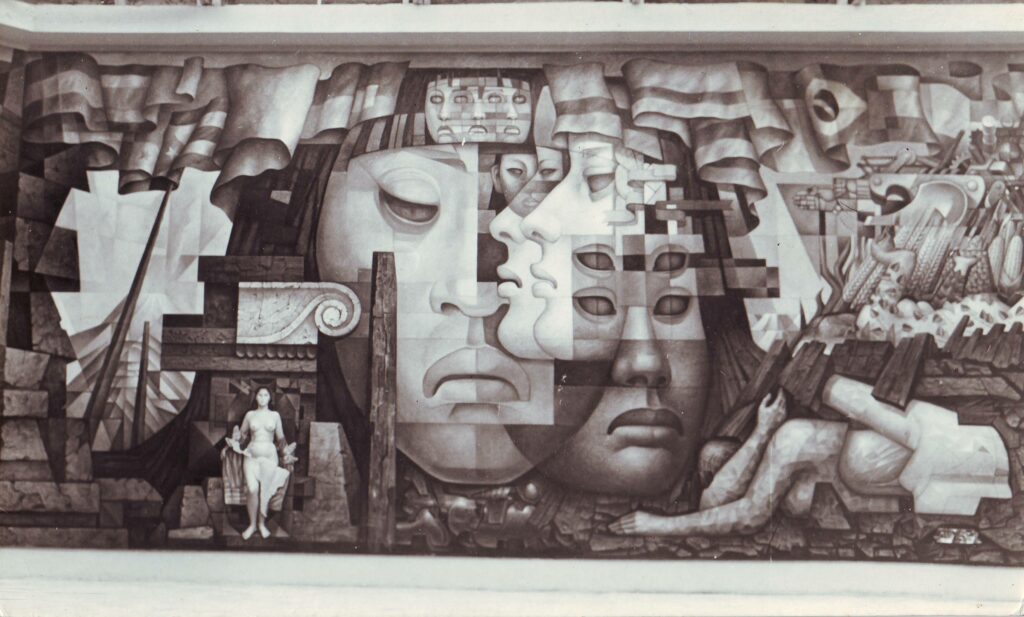

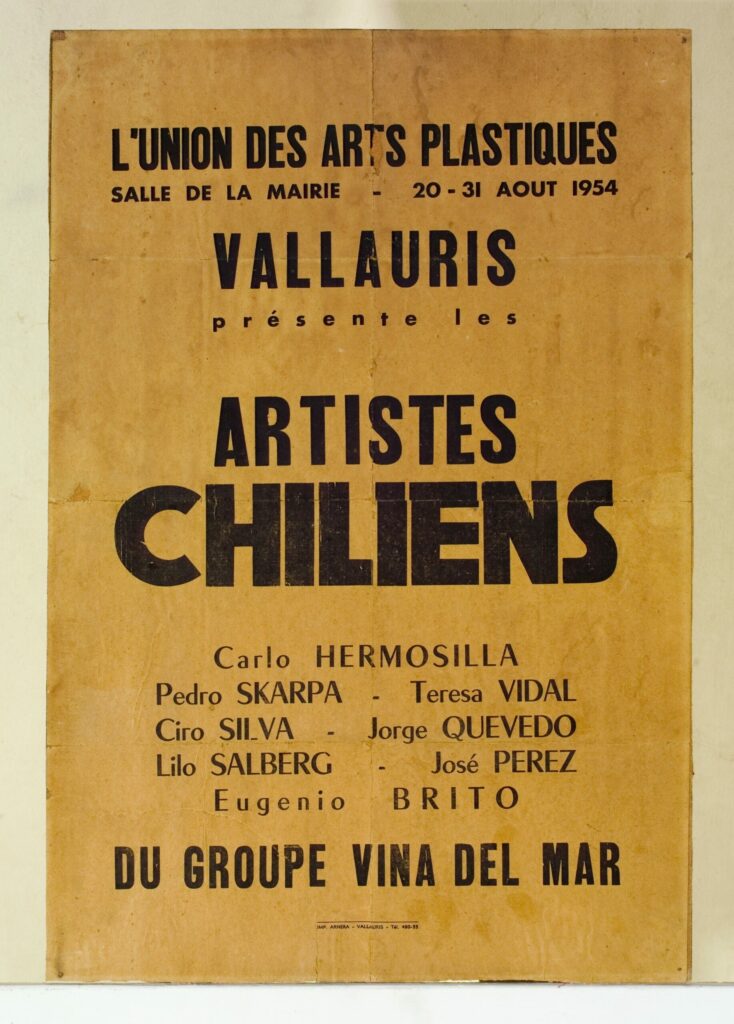

His career in our country, as well as his study tours, were crucial to his development as an artist and teacher. As a result of his extended stay in Paris, he was able to meet poets, writers, and artists such as Picasso, whom he visited at his studio several times. His time in the studio in Florence and his remarkable excursions with the ceramists in Limoges defined and developed his values and abilities. His contact with Mexican master muralists, with whom he shared a passion for direct pictorial discourse on the wall, led to his invitation to collaborate in the execution of the mural at the House of Art of the University of Concepción in 1964, alongside the master González Camarena.

Brito’s experience connected us to particular creative circuits while also encouraging us to dive into our history and the rich intertwining of civilizations that comprise our cultural heritage. He made a positive contribution to the revitalization of certain representational models that had become rather old in academic courses. He also influenced the search for new languages in painting, with a clear trend toward abstractionism, in the deepening of the expressive possibilities of the material, in the incorporation of larger formats in painting, and, most importantly, as a good defender of Americanist themes, in the incorporation of our cultural heritage in the creative process.

Themes developed by Eugenio Brito in his work, particularly in sculpture, limit the theme to the volumetry of the block with a totemic aspect. These sculptures, whether in clay, stone, or wood, are plastically solved based on defined lines and planes to break the light and permeate the matter, with the clear intention of installing a sculptural language linked to the formal synthesis of pre-Columbian sculpture. Most of these pieces show significant origins in native cultures, particularly those from the 1960s, which show an obvious relationship with Mayan steles or Andean ceramics.

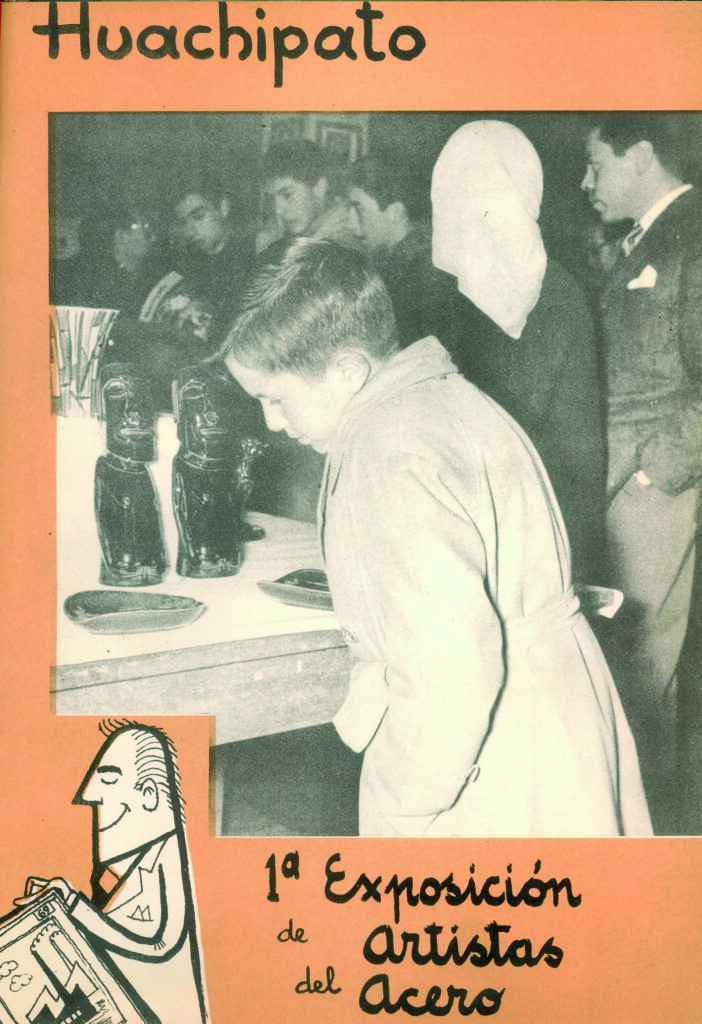

His works on religious topics are particularly noteworthy. The Station of the Cross-mural series, created in clay at the workshops of the Refractory Plant at the Steel Company Huachipato, is mostly figurative and expressive. One of the duplicates can be found in Yumbel’s San Sebastián Sanctuary.

His work, like that of many of his generation, has that distinct blend arising from his knowledge of European art, his academic training, and the impact of our indigenous cultures, which he developed and enhanced during his pilgrimage through Europe and America’s schools and workshops. These experiences and values were offered and shared thoroughly and generously with other artists, his students, and others who knew his quiet and thoughtful creative world during his whole career.