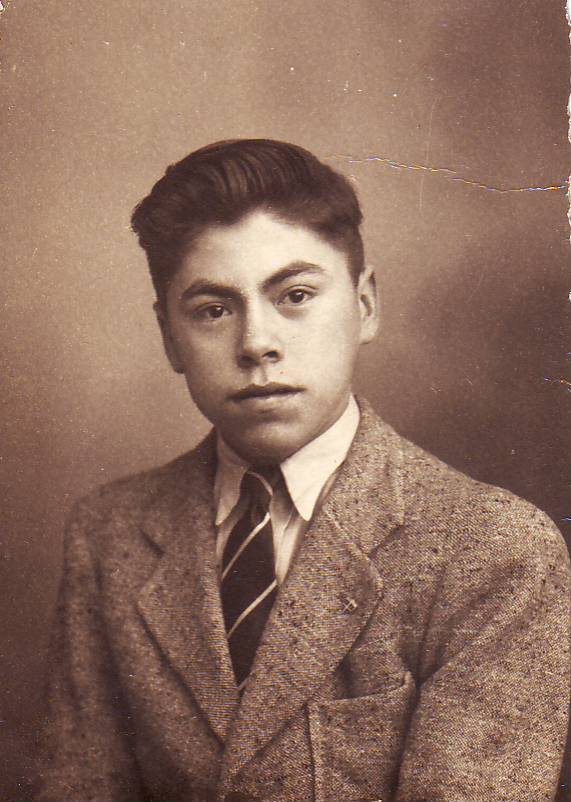

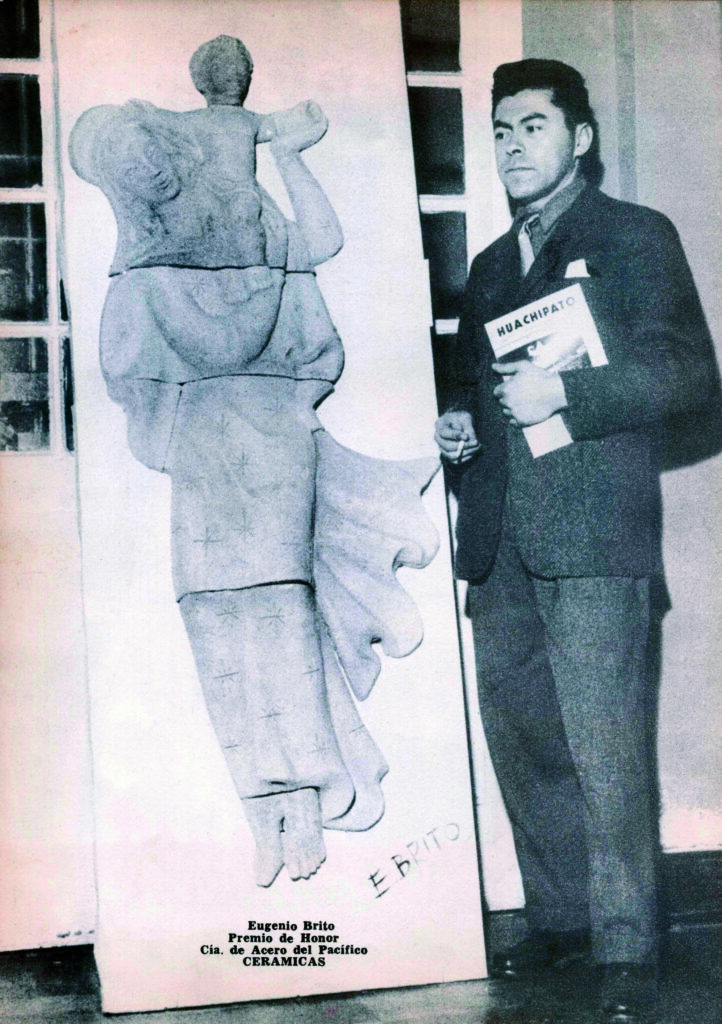

This writing integrates two sources of information that I used to approximate the creative process in Eugenio Brito Honorato’s painting.

On the one hand, there is the testimonial source, where I am an eyewitness to the numerous occasions when I saw him work (in his art pieces), accompanied him, assisted him, and even took advantage of his absence, painting in his work, believing that he would not notice, according to me.

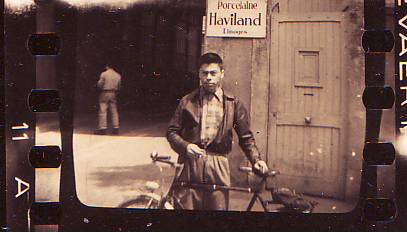

The other source is investigative, in which, after his death, I reconstruct his story around the numerous materials he left, including photographs, writings, notes, sketches, interviews, catalogs, and letters, among others.

Testimony

There are countless memories I have of my father; countless conversations we had; and numerous occasions when I saw him paint, sketch, and investigate, because if something remained etched in my retina and in my being, it was the fact that a painting is the result of a long creative process of reflection and decantation of ideas that were materialized through the language chosen by the artist, in this case, the language of painting.

Yes, I want to clarify that this testimony covers approximately his last ten years, from 1974–75 to 1984, the year of his death. During this period of time, I remember very well the development of several of his paintings and, in its entirety, the creation of his last series of works, called by him ‘Divertimentos,’ which I could have had between my brows to its conception as an idea until seeing them made work.

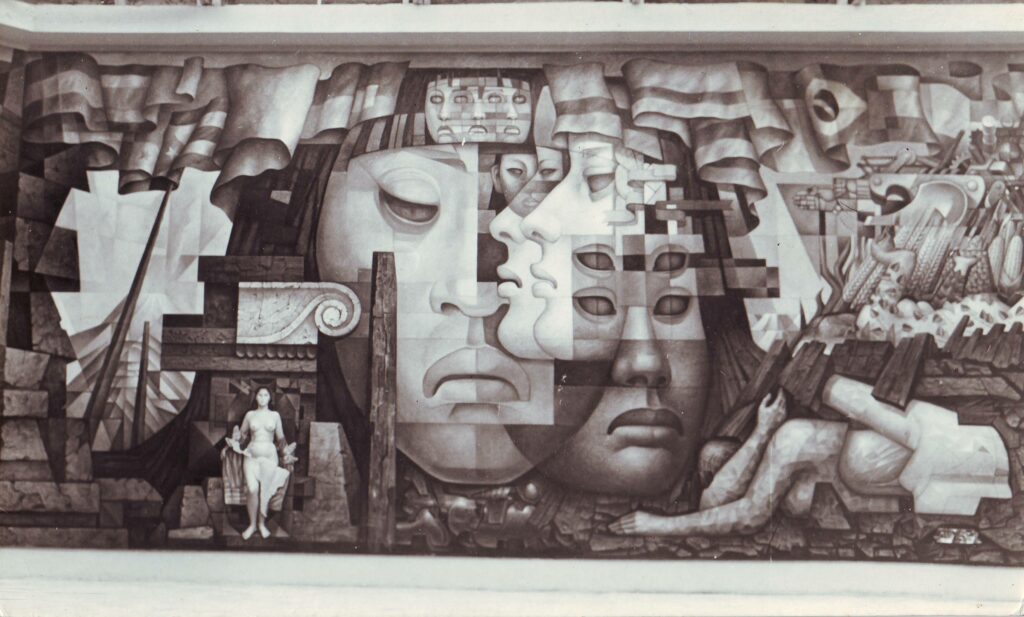

He considered issues, which were questions, concerns, and a common thread that connected everything: man. He appealed to man as a universal being, with his desire to seek ideals and transcendence, to go beyond, which is confronted with reality, which he has constructed, and which, as an absurdity, frequently imposes norms and rules—nonsense that ends with the submission and reduction of man’s most fundamental values. This is referred to as “the dehumanization of man by man.” It is reducing him to a figure, a simple object, another cog in the systematic mechanism, depriving him of freedom, individuality, and decision-making ability, and forgetting, as he stated, that he was a thinking, suffering, and joyful creature.

His picture is introspective, inviting us to pause, reflect, and marvel. It raises concerns and inquiries on the metaphysical level about man’s existence and mission in the world.

I heard him say, ‘I see the artist not as an entity far from reality but rather as a being with his feet very firmly on the ground.’ He (the artist) has a vital duty to do; he must be the moderator, and he must be fair.

The topics he was thinking about, in which man was always the major element, were gradually growing, both in concept and in the countless sketches he did for each painting. In that way, he was very disciplined, methodical, and rigorous, while still allowing for the freedom required for any creative process.

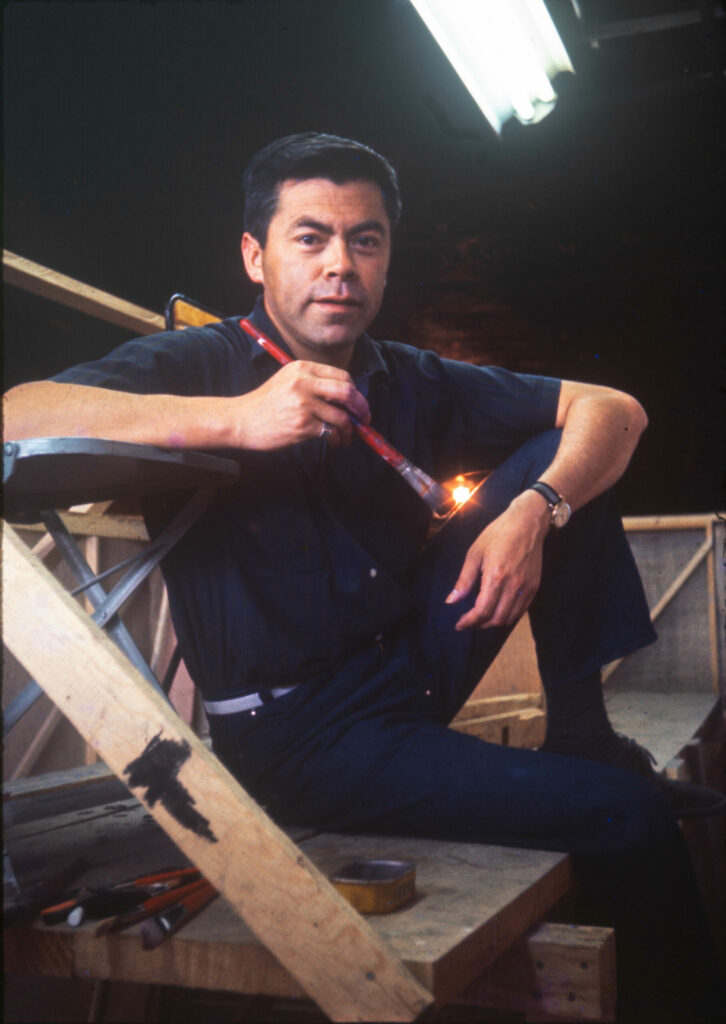

Witness of his work

How could I forget seeing him paint while doing my schoolwork or simply accompanying him? I enjoyed standing next to him, conversing with him, and witnessing the creation of a painting. His calm and clarity in the face of the work he was doing at the time astounded me. Although his painting was ‘rational,’ it allowed for “irrationality,” or, as he put it, “I paint the reality of the unreal.”

I recall seeing him create ‘The Old House in Hualqui’ from the series ‘Radiographies in Time,’ and being able to see how it developed and matured from the sketch “in situ” until it was taken to the canvas. There, it became clear to me that his art is the outcome of a lengthy introspective process and concept decantation.

Divertimentos

‘Divertimentos’ corresponds to his last series of paintings, which he described as “a hoop in the road,” because his previous work was, to put it simply, monumental, and metaphysical. He came to give a slightly more “playful” vision in his painting with this new subject that he had never approached before. He addressed subjects like those dolls that our grandparents played with, those greeting postcards full of fretwork, the bird of luck, and the guardian angel, among others. He drew inspiration for this series from items kept in the trunk of memories.

What motivated him to make this change in his subject? Was it an omen of his soon departure? I think so, because my father was one of those people who had that ‘internal pulse,’ that mysterious and lucid voice at the same time that spoke to him inside, which guided him in his artistic and personal work. At that point, he was already sick with his lungs, and how curious to see in those paintings—practically all of them—the presence of the sky. Could it have been because of that air that his lungs denied him? Or was it that he already sensed the call to the afterlife? He seemed to be in a rush to wrap up this series and meet his deadline; this struck me as odd. It is true that he was painting against time, since he already sensed the call to which all of us are called at some point.

The investigation

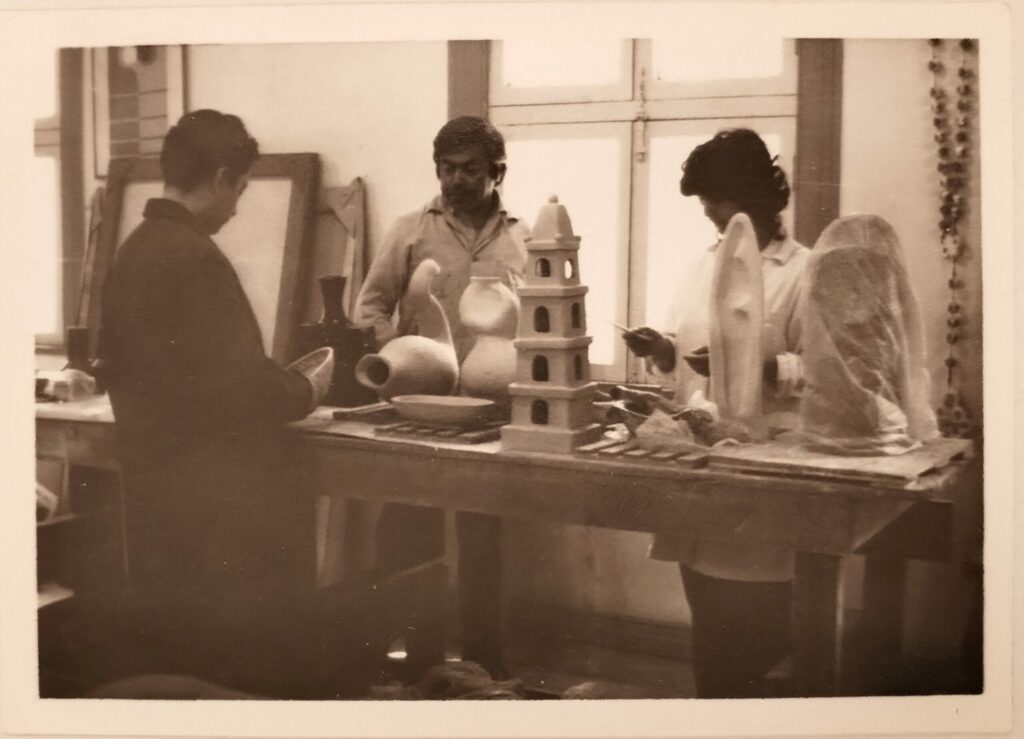

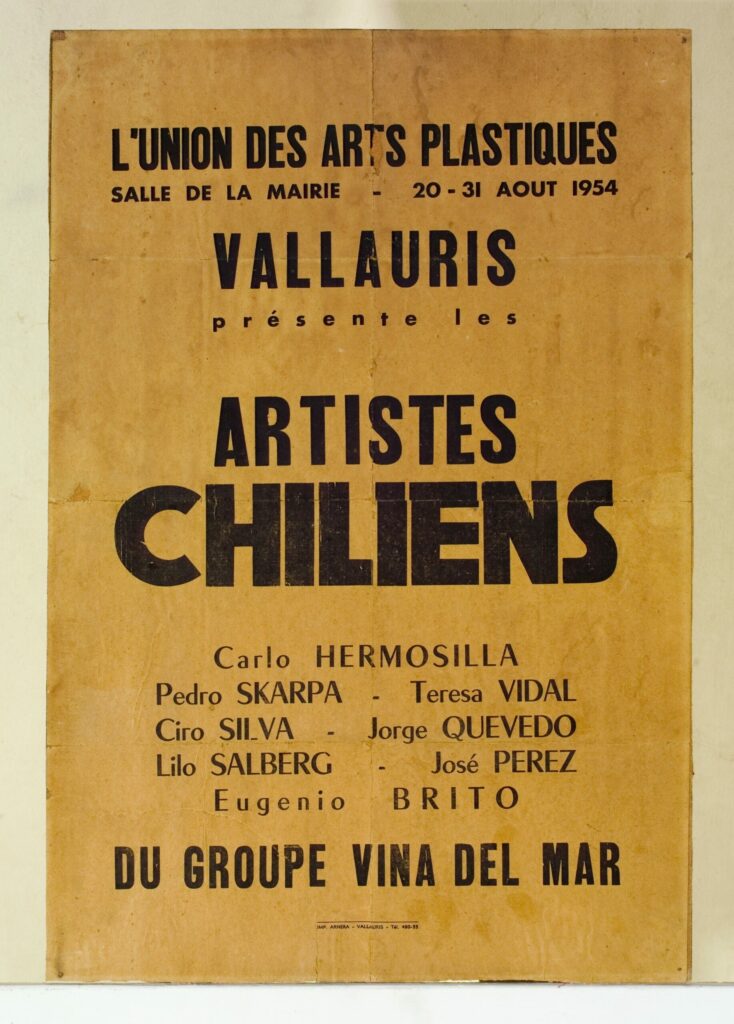

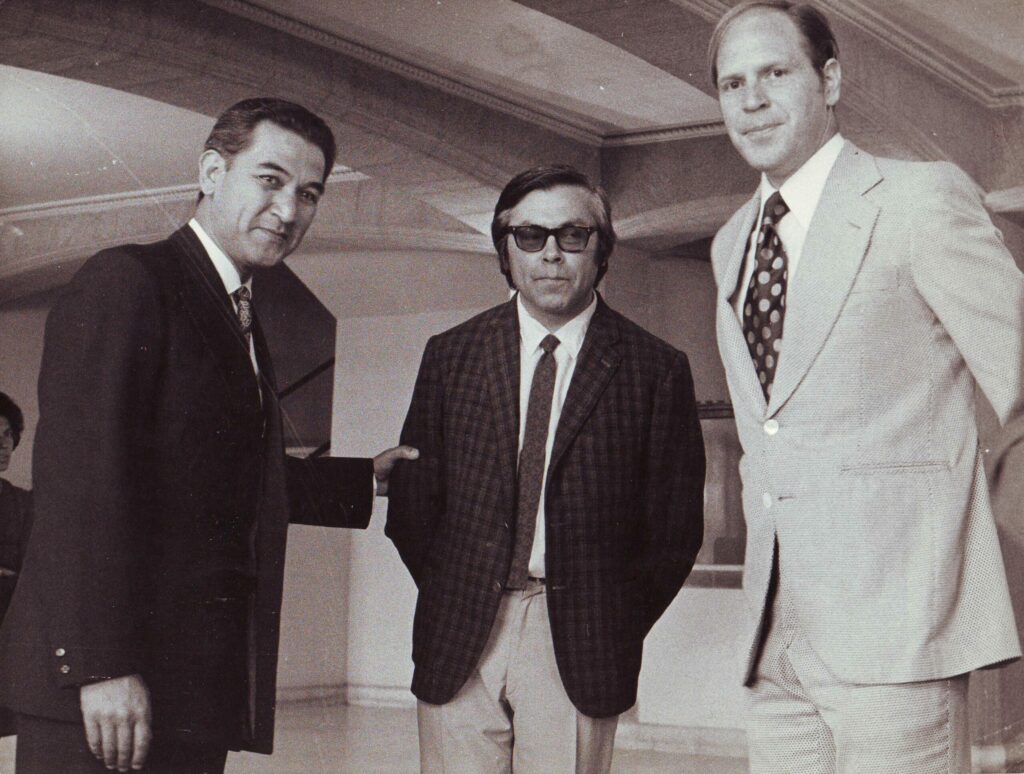

It took a long time after his death for me to meet him again, but this time through the evidence and work he left behind: sketches, poems, photos, letters, notes, and interviews, among other things. It was a re-creation of his life, thoughts, and worldview. It was also a memory. I was able to get to know him better; I was able to comprehend his work, creative process, stages, and numerous characteristics. sculptor, ceramist, designer, engraver, researcher, and collector.

Through his work and philosophy, his anthropological-humanist vision of existence made him a critic of society and current man: “Contemporary man has allowed himself to be put in an archive as if it were a useless document,” says the artist. He wishes to critique human estrangement, the reduction of man to a cold number.”